Learn how to be smarter with this one stupid trick

The mind is a muscle – use it or lose it

Hello, and welcome back to Forked Lightning! If you’re just joining us, last week I wrote about job training for older workers. The week before, I wrote a 5-part series about my recent paper with Raj Chetty and John Friedman on Ivy-Plus college admissions.

This week I want to talk about “soft skills”. Every year the National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook survey asks employers to rate the most desirable qualities in new hires. And every year, qualities like “ability to work in a team”, “initiative”, and “strong work ethic” are at the top of the list. What’s more, employers tend to rate new college graduates highly on technical and analytical skills, but much lower on soft skills.

Soft skills are becoming more important in the labor market. I wrote a paper a few years ago showing that the economic value of “social skills” (e.g. the ability to work with others in a team) more than doubled for a cohort of young people entering the labor market in the 2000s compared to the 1980s. Another paper used administrative data from compulsory military enlistment in Sweden to estimate the economic value of what they call “non-cognitive” skills (I don’t love this term; isn’t everything cognitive at some level?). These are attributes like social maturity, intensity, and emotional stability that were rated on a 1-9 scale after a half-hour interview with a trained psychologist. In Sweden, the economic value of this bundle of attributes nearly doubled between 1992 and 2013.

Meanwhile, the relationship between academic achievement (sometimes called “cognitive” skills) and earnings has remained flat or even declined. In that same Swedish study, the economic return to cognitive skill – as measured by performance of 18 and 19-year-old men on four subtests of reasoning, verbal comprehension, spatial ability, and technical understanding – peaked in the early 2000s and then began a modest decline. A similar study in the U.S. found that the association between scores on the Armed Forces Qualifying Test (AFQT) score – a widely-used measure of cognitive skill – was less than half as large in the 2000s and early 2010s compared to the 1980s and early 1990s.1

The bottom line is that so-called “soft” skills are becoming increasingly valuable. We call them “soft” because we don’t really understand what they are or how to improve them, not because they are unimportant.

Soft Skills are Higher-Order Skills

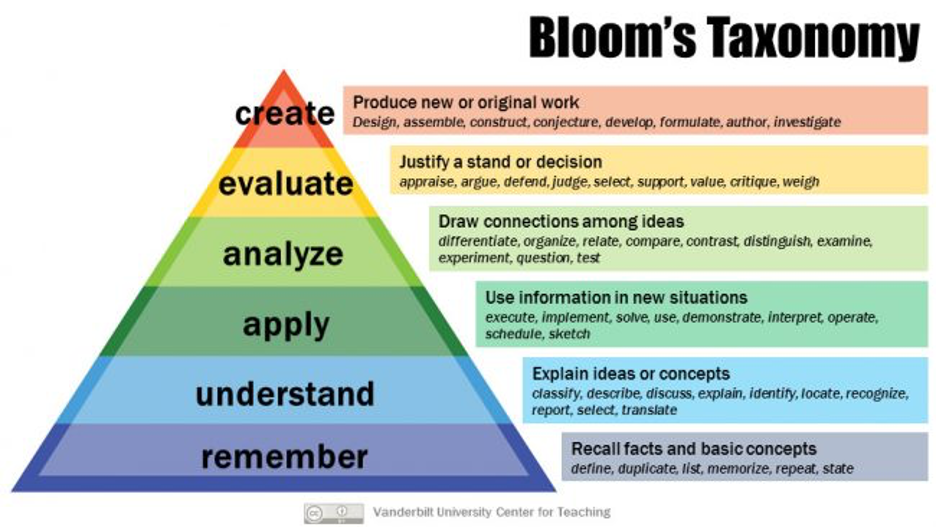

I like to call them higher-order skills, following Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Bloom’s taxonomy is a hierarchy with factual knowledge at the base of the pyramid, followed by increasingly sophisticated integration of the knowledge “base layer” into cognitive concepts like understanding, application of knowledge to new situations, synthesis and evaluation, and creativity. It was original developed in 1956 by a team of cognitive psychologists (Benjamin Bloom was the chair, hence the moniker) and revised further in 2001. The revision (shown here) put creativity at the top and changed nouns into verbs.

Most tests used in school focus on the bottom two layers of the pyramid. This includes state achievement tests in subjects like math and reading, but also college preparatory exams like the SAT as well as the AFQT mentioned earlier. Can you regurgitate facts on command? Can you comprehend passages of text or perform basic mathematical operations that demonstrate understanding?

Yet when employers say they want to hire good problem-solvers or team players, they are moving beyond understanding and remembering, into the upper floors of the pyramid. They want people who can use information in new situations to justify a stand or decision (problem-solving) and draw connections between other people’s ideas to produce new or original work (teamwork).2

It’s clear that we should try to build higher-order skills in school. But how? When teaching the basics – reading, writing, arithmetic – we have clear definitions of the underlying concepts and well-established ways to track progress. In contrast, soft skills are like pornography (in only this one way!) – you can’t define it, but you know it when you see it.3

What is “grit”, and how do we teach it?

Grit is a useful case study in the limitations of a “you know it when you see it” definition of soft skills.

The concept of grit was popularized by the psychologist Angela Duckworth, whose 2016 book “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance” sold more than a million copies and set the education world ablaze. Her book showed that grit was an important predictor of success in a variety of settings, ranging from college GPA to dropout rates among West Point cadets and ranking in the National Spelling Bee.4 Following the publication of the book, schools across the country put grit posters in the hallways and even included grit ratings on report cards.

Duckworth defines grit as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals.” Webster’s dictionary defines it as “firmness of mind or spirit: unyielding courage in the face of hardship or danger.” Based on my understanding of how it is used in educational contexts, I’d define grit as the ability to persevere through demanding, sometimes unpleasant tasks to achieve a desired long-run outcome.

Grit sounds amazing – how do we teach kids to be grittier? One view treats grit as a state of mind. Learning is hard. If I think my intellectual ability is fixed, then studying something challenging may not be worth it, because I’ll never catch up. But if I think of my mind as a muscle that gets stronger with practice, perseverance today will be rewarded tomorrow. That’s growth mindset, a concept popularized by psychologist Carol Dweck and applied extensively in American classrooms as part of a suite of social and emotional learning (SEL) initiatives that have received increased state and federal funding in recent years.

If grit is a state of mind, it follows that changing students’ beliefs about the returns to study effort will yield success. Yet the evidence from growth mindset interventions is mixed at best. The Psychological Bulletin, a major journal that publishes reviews of research topics in Psychology, published two different meta-analyses (these are studies that review the evidence across multiple studies) of growth mindset interventions.

Even though they were published only three weeks apart, the two meta-analyses reached different conclusions. One found positive impacts for low achievers (but not for other students), while the other reached the more skeptical conclusion that the only time such interventions work is when the researchers had financial interests in their success. Not exactly glowing reviews.

The two growth mindset studies that I know best also reflect this ambiguity. A carefully done national study by David Yeager and colleagues found small, positive impacts on 9th grade GPA, but only for low achievers. Another carefully done study by my former student Alejandro Ganimian found no effects at all of growth mindset interventions on 12th grade students in Argentina.

Why don’t growth mindset interventions produce better results? I think the answer sits in the liminal space between intentions and actions. Adopting a growth mindset is a necessary – but not sufficient – step toward become grittier. If I think capabilities are fixed, I certainly won’t put in the work to try and improve. But even if I believe my mind is a muscle, I still need help learning how to flex it.

A randomized trial involving 52 state-run elementary schools and 3,200 4th graders in Turkey found that an intervention designed to improve grit had a large impact on math scores.5 Importantly, about two-thirds of the impact persisted two and a half years later. This study, unlike some others, paired growth mindset training with structured goal-setting support, and they engaged children in deliberate practice for two hours per week over the course of twelve weeks.

In other words, they didn’t just tell children that their mind is a muscle: they also put them in the gym and helped them get to work.

Cognitive endurance

We see this vividly in a recent study that randomly assigned 1,636 low-income Indian primary school students to two types of effortful cognitive activity: one that is clearly academic, and one that is not. One experiment group was assigned to 20 minutes of challenging math problems a few times a week during the school day. The second group was assigned to 20 minutes of cognitive challenging activities like tangrams or maze puzzles. These activities required cognitive effort but were not otherwise part of the school curriculum. A third control group was assigned to a study hall. The authors found that both experiment groups had higher grades, and the impacts persisted for several months, even after students returned from an end of year break.

Most interestingly, the impacts on performance in both groups were largest at the end of the exam, when “cognitive fatigue” sets in. Think about what this means – 1 hour per week of practice in sustaining mental effort on an unrelated task improves performance at the end of a math exam several months later. The authors call this mechanism “cognitive endurance”, and they show supporting evidence that cognitive endurance matters a lot in other contexts.

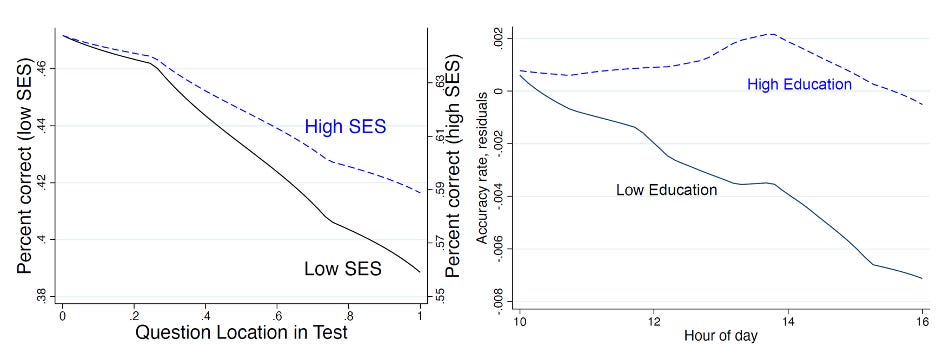

In a global sample of kids taking the PISA, an internationally normed reading test, high SES kids exhibit smaller performance declines at the end of exams than low SES kids (the left panel). Looking at adults working in data entry, performance declines less over the course of the day for more educated workers (the right panel).

Cognitive endurance reframes grit as a skill that is developed through practice rather than as a mindset to be shifted. The difference is more than semantic. If we are going to build higher-order skills in children, we need to better understand the science of how to do it.

It has taken more than 100 years to develop a science of teaching reading, and even today, lots of ink is spilled on how to do it better. Why should we expect anything less for grit, or teamwork, or problem-solving? More research is needed to take the “soft” out of soft skills.

The survey most often used for such comparisons is the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), which collects data from two cohorts of adolescents, one beginning in 1979 and the other in 1997. This was the data source used in the Bell Curve, where the AFQT was (incorrectly in my view) used as a proxy for IQ. It is more like the Swedish test, which measures some combination of reasoning ability and knowledge.

Does that mean we should restructure schooling to emphasize the development of higher-order skills? Not necessarily. As the pyramid structure implies, these foundational capacities are a necessary condition for developing higher-order skills. We memorize single digit multiplication tables – and learn simple algorithms for 2-digit multiplication and long division - because we use these processes so often as inputs into more complex problems. Memorization of facts or processes saves cognitive bandwidth. You can’t be a good actor if you spend all your effort on stage trying to remember your lines.

Hat tip to Alan Novak, Justice Potter Stewart’s law clerk.

Fun fact – my younger brother competed in the National Spelling Bee. He finished 30th. His elimination word was “geodesy”. My mom’s team won the parents’ bee that year. Go Dan! Go Mom!

The initial effect size was 0.31 standard deviations (SDs), and the impact after 2.5 years was 0.23 SDs. How big is that? The Tennessee STAR experiment reduced kindergarten class size from 22 students to 15 students, which led to an increase in test scores of 0.2 SDs and a 7 percent increase in the probability of going to college. So a persistent increase in match scores of 0.23 SDs is a very large effect. However, the authors found no impact on persistence for reading scores.

"Grit" sounds useful, but absent "cognitive" skills, "soft skills" ain't scalded no hogs. Considering your timeline which overlaps a lot of deindustrialization and "shift to service economy," how much of the value of "soft skills" you discuss here is simply rewards for filling "bullshit jobs" a-la Graeber (see https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/the-bullshit-job-boom ), those being jobs in which workers do not produce anything useful but rather "produce" a lot of getting-along-with-the-boss and other bullshit? "Soft skills" are the skills required for bullshit jobs, not productive work, so even if training can inculcate "soft skills" into would-be workers, those may not lead to any real productivity in the economy.

A very accessible distillation of a lot of complex research. Well written! Where I think this piece goes wrong - and your footnote 2 and Bloom pyramid feed into this - is to assume all learning works like math (the example used every time to justify this building blocks way of thinking). What this leaves out is the research on importance of “situated cognition” - that the context in which learning happens matters a lot. This turns out to impact both for how new knowledge and skills are incorporated into memory so they can be used later, and in establishing and maintaining motivation in fostering engaged learning. Starting with an authentic problem that is engaging for learners and then working backwards to the skills needed to solve that problem can be a powerful and effective approach that flows in the opposite direction of bloom.