Ivy-Plus colleges are a gateway to the elite

Is all this competition to get in really worth the effort? Probably, yes.

What is the benefit of attending an Ivy-Plus college?

Most coverage of our paper has focused on the question of who gets admitted to Ivy-Plus colleges and why. Today I want to focus on the second part of the paper, which asks whether attending an Ivy-Plus college benefits students who are admitted.

You might think the answer is obvious. Given how much effort families undertake to get their kids admitted, it must be worth the trouble! But the prior research on this question is decidedly mixed. Dale and Krueger (2002) famously found that there was not much impact of attending a more selective college, except for disadvantaged applicants, and a recent paper by Mountjoy and Hickman (2022) finds a similar result using data from Texas public universities.

On the other hand, there’s lots of other evidence of high returns to attending a four-year college, or to attending any college at all. One of the best studies is by Seth Zimmerman, who finds that students who attend Florida International University (the least selective four-year college in the state at the time) rather than a community college or no college at all have 22 percent higher earnings a decade later. A few other studies find similar results.

These studies exist because most schools don’t have the resources to practice holistic admissions. Instead, they use cutoffs (sometimes public, sometimes hidden) based on test scores, GPA, or the two in combination. Zimmerman compares students on either side of a 3.0 GPA cutoff and ask whether those who were just barely admitted do better than those who were just barely rejected. Roughly speaking, evidence of a positive impact comes from a sudden increase in earnings right at the GPA admissions threshold, which can only be caused by the sudden change in attendance.

The Waitlist – Choosing Among Equals

This is a very clean research design, and we would love to have copied it. But the admissions process at Ivy-Plus colleges does not obey such simple rules. So we use the next best thing – the waitlist. If FIU kept a waitlist, we’d expect it to be ranked in order of GPA. The Ivy-Plus colleges in our sample do not rank their waitlist, but all the applicants on it look roughly equally qualified.

Still, only about 3 percent of the waitlist are eventually admitted. Are the admits more qualified than the rejects? No, at least not on any of the dozens of academic attributes we observe in the data. We verify this directly by showing that admission off the waitlist at one college does not predict admission at other colleges (we refer to this in the paper as the “multiple rater test”).

More pointedly, waitlist rejects from one school are just as likely to get into another school as waitlist admits, and much less likely to get in than regular admits.

What is going on? Our sense from the data, from other case studies of elite college admissions, and from talking to admissions officers at length is that admission off the waitlist is mostly about class-balancing and (to some degree) yield management. Colleges want a class that is broadly representative along many different dimensions, and if certain admits turn them down, they will look for others on the waitlist with similar characteristics (playing a certain instrument or sport, being from a particular state, etc.). [1]

It's not exactly random, but it is idiosyncratic, and probably unrelated to future life success. The class balancing rationale also explains why our “multiple rater” test works – being admitted to Princeton because you play the saxophone and the first-choice saxophonist turned down her admissions offer is not going to predict whether you are also admitted to Yale. Likewise, the only reason why playing the saxophone rather than the flute would predict future earnings is if it happened to luck you into a spot off the waitlist at a highly selective college.

In other words, within the waitlist, we have a sample of applicants who are equally worthy in the eyes of the college. We can then treat it like the case of Florida International, where the only plausible explanation for differences in outcomes is that some applicants were admitted and others were not.

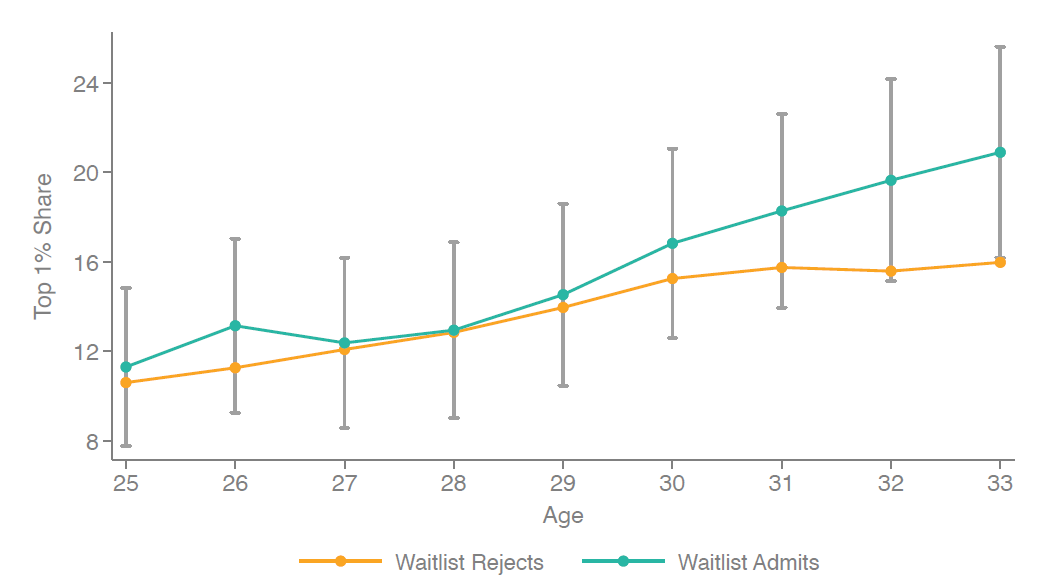

Figure 12a shows the share of waitlist admits and rejects who reach the top 1% of income for their age, for ages 25 to 33. There is a clear pattern of divergence for applicants who are admitted, and by age 33 they are much more likely than rejected students to earn incomes in the top 1%. One reason it takes so long for the impact on top earnings to emerge is that graduate school attendance is very common. Figure 12b shows that waitlist admits are also much more likely to attend an elite (top 10) graduate school between the ages of 25 and 28. [2]

Figure 16 is a useful summary of our main results. Waitlist admits are 60% more likely than waitlist rejects to have earnings in the top 1% for their age, are nearly twice as likely to attend a top 10 graduate school and are three times as likely to work in a prestigious firm (think highly ranked research hospitals, top law and consulting firms, national newspapers, etc.).

The other nice thing about the waitlist design is that it answers a very interesting question – if we expanded class size by a few more students (meaning more of the waitlist rejects could be admitted), what would be the benefit to them? Our results suggest that Ivy-Plus colleges could expand the pool of admitted students significantly without compromising on the quality of their incoming classes. I’ll have more to say about that later in the week.

Dale and Krueger didn’t have the right data to study the top 1%

Dale and Krueger take an entirely different approach, which we call the “matriculation design”. They look at differences in outcomes between people who were admitted to the same colleges but made different choices. For example, is the impact of attending Harvard relative to Ohio State different for applicants who were academically qualified enough to be admitted to both? Perhaps surprisingly, a sizable minority of student opt against attending the highest-ranked college to which they were admitted. Still, looking at students who are talented enough to be admitted to Harvard but choose to go elsewhere seems like a good way to sort out whether Harvard is “adding value” or whether they are just picking kids who are going to succeed regardless of where they go to college.

Using this “matriculation design”, Dale and Krueger find no impact of attending a more selective college on average earnings. Our findings from the waitlist design are similar to theirs for average earnings – a small positive effect that is barely different from zero even in a very large sample. The problem is that the survey they used (called College & Beyond) collected earnings data in a way that makes it impossible to study very high earners. Earnings were self-reported within broad buckets ($50k to $75k, $75k to $100k, etc.) and the top category was “more than $200k”.[3]

When we apply the Dale and Krueger matriculation design in our data, we replicate their result - small or zero impacts on mean earnings. However, with the increased precision in the tax data and a bigger sample, we find large impacts on having top earnings, attending a top graduate school, and other outcomes. Encouragingly, the magnitudes from the matriculation design match our waitlist design very closely, even though we are making a completely different comparison.

I conclude from this that Dale and Krueger would have found the same thing we found if they had data like ours. There’s no inconsistency between studies, they just didn’t have enough precision.

Tomorrow I’ll talk about why we find such big impacts at the top end for Ivy-Plus graduates, focusing in particular on the role of on-campus recruiting.

[1] In the paper we also look directly at whether the waitlist is balanced on applicant characteristics. The answer is mostly yes, with two exceptions. First, waitlist admits have slightly lower test scores and academic ratings than waitlist rejects. Second, waitlisted legacies and applicants from the top 1% of family income are more likely to be admitted. That turns out not to matter very much, both because legacies do slightly worse than non-legacies and because we get the same (if anything, slightly bigger) results when we exclude legacy and high-income applicants from the analysis. All the gory details are in the paper.

[2] You may wonder about the alternative for waitlist rejects – what if they attend another Ivy-Plus college instead? We scale the magnitude of our estimates using differences in outside options across applicants. Intuitively, think of UC-Berkeley as the backup plan for students applying from California, and Ohio State as the backup for students applying from Ohio. Since Berkeley has a bigger impact on earnings than Ohio State, the impact of being admitted off the waitlist for students from OH should be higher than for students from CA. Figure 13 formalizes this intuition and scales our waitlist estimates to reflect the difference between attending an Ivy-Plus college and one of the 9 most selective public flagships, which we think is a reasonable comparison.

[3] A more subtle issue is that they assumed that better colleges were the ones with higher average SAT scores, whereas we measure college “value added” on earnings directly.

But doesn't your assumption depend upon elite colleges acting independently of each other in admissions, when we know historically that they colluded in an anti-competition conspiracy?

The elder Bush's Administration sued Ivy League colleges for collusion: holding an annual conference at which they decided who gets which admits. The Clinton Administration later dropped the suit, but the colleges announced they wouldn't do it anymore.

Can we trust their non-binding declaration?

So if the admit cohort is overrepresented in the top 1% of incomes, but shows no difference in mean incomes, for what ranges of incomes are the reject cohort overrepresented relative to the admits? Are the admits overrepresented at the low end of the spectrum as well?