Welcome back! In case you’ve just joined, yesterday I dug into our methodology for measuring the benefits of attending an Ivy-Plus college. Today I’ll talk about why the benefits of attending an Ivy-Plus college are so big for some people.

One of the most interesting findings in our paper was that while Ivy-Plus students are much more likely to have top 1% earnings, their average earnings are not too much different than students who attend selective public universities.

This is because public university graduates mostly earn incomes in the 70th to 95th percentile – very good, but not at the top.

Before diving into the reasons, a quick word on magnitudes. We find small impacts on mean income rank, but the value of a “rank” is different at different places in the distribution. The difference between 78th and 79th percentile (the average for people who attend selective public flagship schools) is about $2,000 per year, but the difference between 98th and 99th is almost $40,000 per year. We find mean impacts of about 1.5 ranks, or an increase of about $3,000 relative to a base of around $60k. But we also find that Ivy-Plus students are much more likely to get to the 99th percentile of income and beyond.

Is that a big impact, or not? Think of it like winning the lottery. Suppose I told you and 9 of your closest friends that one of your group of 10 was going to win a prize - let’s say $1 million. But I don’t divide the tickets evenly. Since you attended an Ivy-Plus college, you get 2 tickets. Friends who attended a selective public university get one ticket, and those who didn’t go to college get none. Your odds are double anyone else’s, but you still probably won’t win. I increased your expected earnings. Going to an Ivy-Plus college gives you more chances to hit the jackpot. But among non-jackpot winners, things look pretty similar regardless of where you went to college.

So why do Ivy-Plus students get more lottery tickets? Perhaps an elite education helps you climb up the corporate ladder using classmate and alumni connections. A clever study collected archival data from Harvard in the 1920s and 1930s and found that members of exclusive “old boys” clubs had much higher adult earnings and were much more likely than other students to work in finance. [1] They also found that the benefits mostly accrued to members who also attended exclusive private high schools, which suggests that the old boys’ social network was driving later success. Another study found large impacts on top earnings for people who attended an elite business-focused degree program in Chile, but that the benefits were concentrated entirely among males who previously attended exclusive private high schools and formed close peer ties. [2]

Social ties may indeed be very important, especially for top positions in business leadership. However, I don’t think social ties alone can explain our results.

Digging deeper into the data, we see that a college applicant’s employer at age 25 very strongly predicts their own earnings at age 33. So strongly, in fact, that we can use it to increase the precision of our estimates. Not very many of the applicants in our sample have even turned 30 yet, the age where earnings tend to stabilize and graduate school attendance is mostly complete (unless you are getting a PhD, or as my friend Jeff Smith often says with a smirk, you are a “gradual” student).

Instead of using actual earnings at age 25, we ask “are you working at a firm that paid very high salaries to other 33-year-olds in the past?” Of course this is only an approximation, but the fact that we find similar results for the smaller number of students where do see earnings at 33 gives us confidence that this is a sensible workaround. [3]

Although using predicted income was a practical choice, the fact that it works so well explains a lot about what is going on. At age 25, most graduates are still working in the first job they took after college. They aren’t CEOs or top managers, but rather fresh meat for the corporate grinder. So to understand our results, we need to know more about the kinds of firms that hire Ivy-Plus graduates right out of college.

We create a measure of firm “prestige”, which roughly speaking corresponds to being the kind of employer that hires a lot from the Ivy-Plus but not much from public universities. Now you may ask – isn’t that a little bit circular? What if the Harvard college bookstore employs a lot of Harvard graduates but no Buckeyes – wouldn’t it be prestigious by your definition?

We do a few things to account for this possibility, the details of which are buried deep in Appendix D. But as a sanity check, we compare the firms that we call “prestigious” to other external lists. Here is a list of top consulting firms – here’s the list for law, for investment banking, and for top hospitals and medical research institutes. Of the 10 largest employers in each category that our analysis calls “prestigious”, more than half of them also show up in the top 10 of these lists. I can’t reveal the actual firm names, but trust me, they match your intuition.

Here's how to think about it.

If you want to work in finance, graduating from Ohio State gets you a great job at a regional operation like Huntington Bank or Nationwide Insurance. If instead you graduate from Harvard, you work somewhere like Goldman Sachs. For consulting, the comparison might be Deloitte vs. McKinsey. In journalism, it’s the Columbus Dispatch versus the New York Times. The point is that there are a small number of nationally recognized prestigious firms which provide a gateway to high-earning and high-status occupations. [4]

On-Campus Recruiting

And boy, do these firms spend a lot of time hanging out on Ivy-Plus college campuses! At Harvard, the three most prestigious management consulting firms – McKinsey, Bain, and Boston Consulting Group – interview students in their sophomore year for internships the following summer, which often lead to formal job offers shortly thereafter (Yale and Princeton follow a similar pattern, with recruiting events held as early as freshman year). In 2022, 40% of Harvard graduates and 30% of Yale graduates went into consulting or finance.

Aden Barton wrote a wonderful article in the Harvard Crimson on this subject, which you should really read in full, provocatively titled “How Harvard Careerism Killed the Classroom”. He argues that careerism is driven by the increasingly brutal competition to be admitted. Having worked so hard to earn their spot, Harvard students feel intense pressure to have something to show for it. He also highlights the many ways that students are unconsciously funneled into finance, consulting, and technology jobs. These firms recruit early and often, promising the security that students crave, and in contrast jobs in the nonprofit and public sectors are hard to learn about and aren’t filled until students are very close to graduation. This matches my sense from talking with the students I know well. It’s not just the money that matters, but also the security of knowing what you are going to do next.

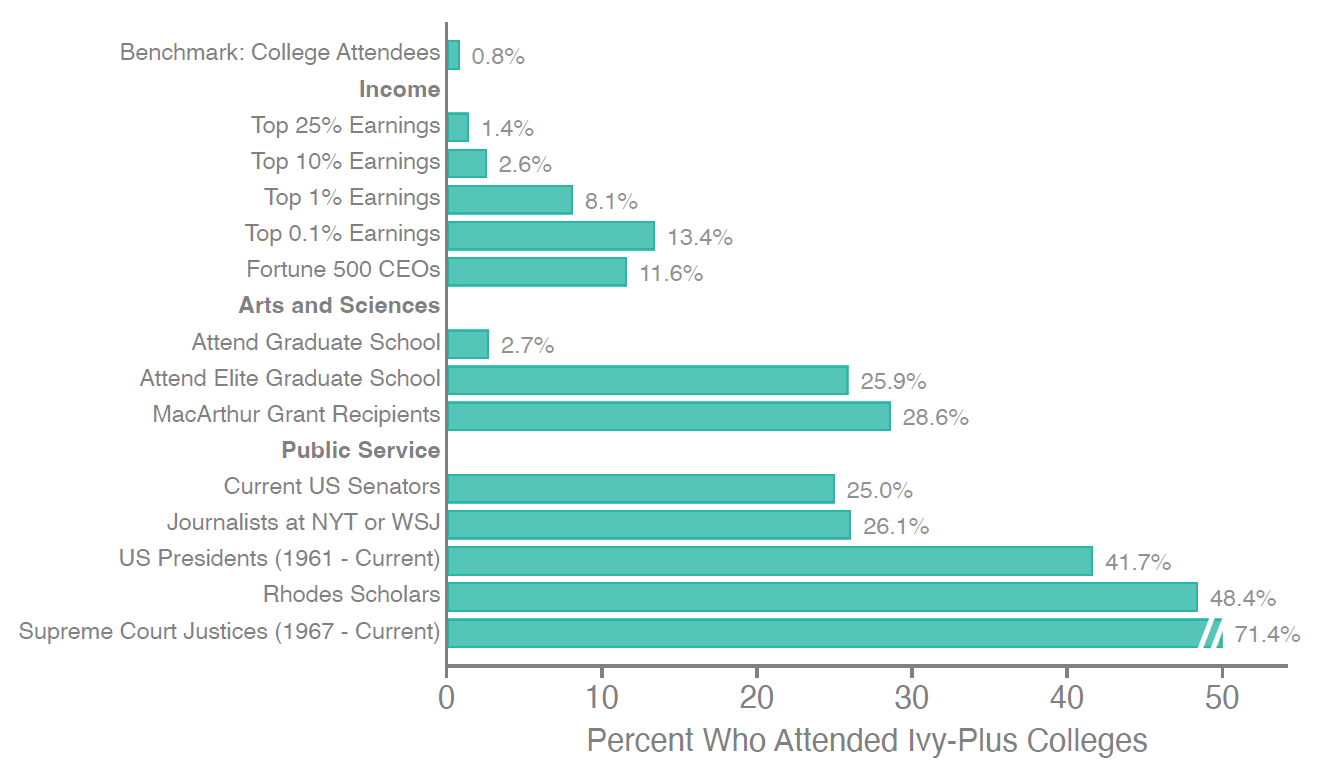

The concentration of prestigious employers is not only limited to industries that pay extraordinarily high salaries. A recent study found that 1 in 4 journalists at the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal attended an Ivy-Plus college. Ivy-Plus graduates constitute 1 in 4 current U.S. senators, nearly half of all Rhodes scholars, and almost 30 percent of MacArthur “genius” grant winners. (This is all in Figure 1 of the paper, shown below.)

The 12 Ivy-Plus colleges educate less than one percent of U.S. college students, yet their graduates occupy a hugely disproportionate share of high-earning and high-status positions in society. That’s an incredibly narrow talent pipeline. The importance of first job after college suggests that on-campus recruiting practices could be a key lever for change.

Tomorrow we’ll take on holistic admissions, the approach of evaluating candidates on multiple dimensions in order to discern who is most deserving of admission.

[1] They are actually called “final” clubs. Still, the term “old boys club” is a highly demographically accurate portrait of these clubs from 100 years ago, when nearly all members were white, male, and aristocratic. They still exist today, and while they are much less white and male, they are still highly exclusive.

[2] Both studies were written by Seth Zimmerman, whose work I also discussed in the prior post. Go Seth!

[3] Interested readers can check out Appendix C of the full paper, which describes the prediction method in glorious detail.

[4] The sociologist Lauren Rivera has some really interesting work showing the ways that elite firms hire based on “cultural match”, which often favors white and high-income applicants. The logic probably also applies to Ivy-Plus colleges to the extent that you learn about elite culture by spending time at an elite university.

Great article but stop with the, if we recruited at other campuses narrative. Elite employers are focused on getting the smartest kids. That’s the game.

My intuition is not that too much power is concentrated in the hands of a small number of colleges, it is that to much real world power is concentrated in institutions centered around the financial business. The colleges are just their recruiting agencies. I also intuit that the second concentration is caused by the financial demands of the Federal Government.