A Young Person’s Guide to Larry Katz

What 35 years of groundbreaking research on education, neighborhoods, and inequality has taught us

Welcome back to Forked Lightning! If you’re just joining us, last week I wrote about soft skills and the concept of “grit”. The week before I wrote about job retraining for older workers, and the week before that was my multi-part series about admissions at highly selective colleges. Check it out!

This week I want to talk about Larry Katz, a man who has a profound influence on my scholarly career and on the careers and lives of countless others. The impetus is a chapter that David Autor and I just completed for the Palgrave Companion to Harvard Economics, entitled “A Young Person’s Guide to Lawrence F. Katz”. If you are an economist (current or aspiring), or a person who cares about education, skills, technology, labor markets, neighborhoods, or economic inequality (which seems likely, given that you’re reading this newsletter), you should really read the entire paper.

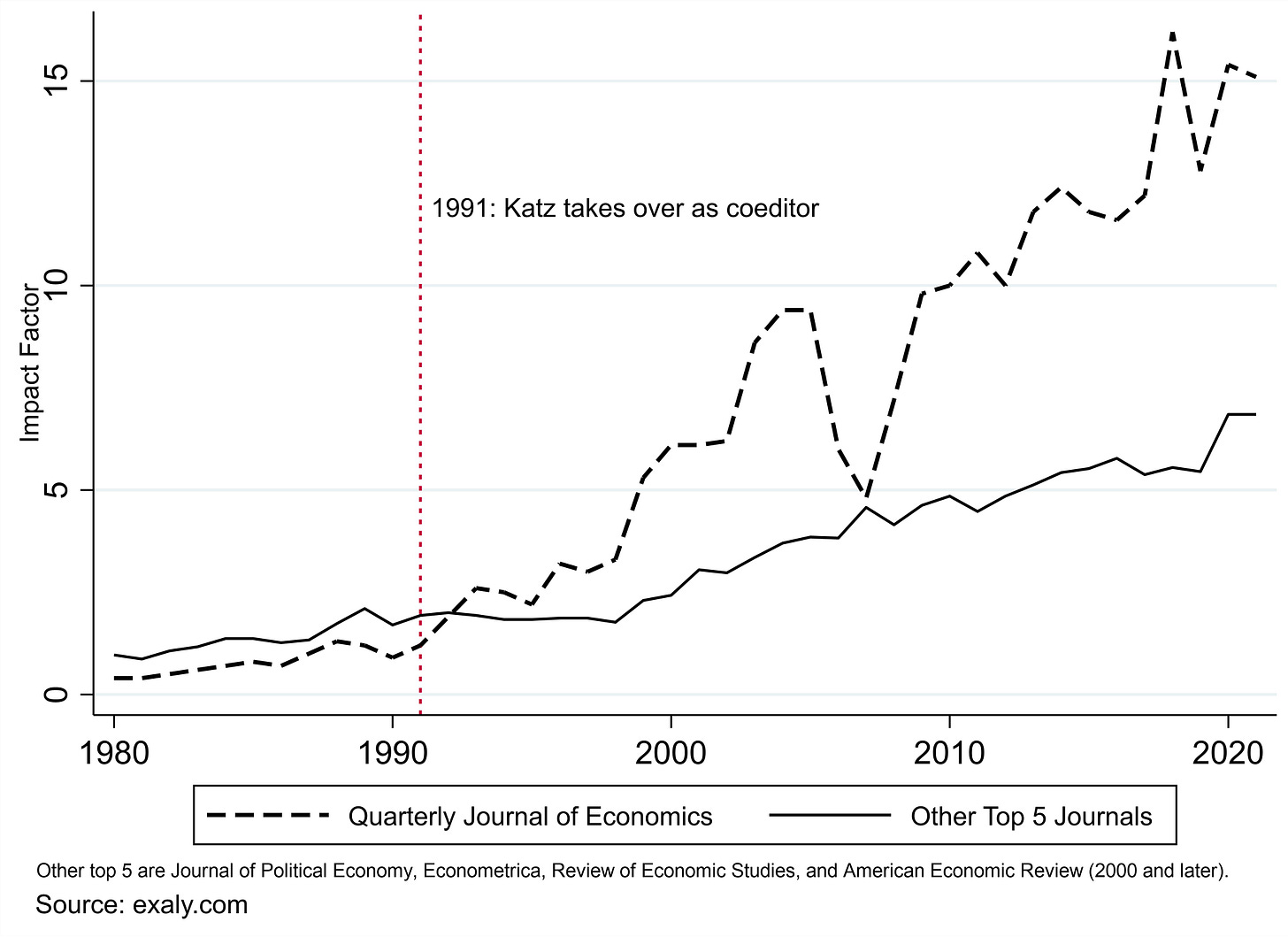

My purpose today is partly tribute, and partly intellectual history. Larry is responsible for some of the most important ideas and findings in modern labor economics. He’s also served as a steward of the profession through his editorship of the Quarterly Journal of Economics and his mentorship of more than two hundred PhD students over the years, two of whom are David Autor and me. In his time at Harvard, Larry has served on an average of 6 dissertation committees per year. That’s staggering! He’s advised multiple John Bates Clark medal winners and MacArthur “genius” grant winners and dozens of scholars at top economics departments all around the country.

The Quarterly Journal of Economics is the top journal in economics, with an impact factor nearly double the next highest competitor. But it was not always so. When Larry took over as coeditor of the QJE in 1991, it was ranked below the average of the other “top 5” journals.1 As the figure below shows, the “treatment effect” of Larry Katz in an event study framework is positive and (probably) statistically significant. By 2022, the QJE had an impact factor more than double the average of the other top 5 journals.

I will praise Larry in this post because he deserves it. But I also want to use this opportunity to explain two important lessons that we should all learn from Larry’s work.

The first half of my Katz encomium focuses on his contribution to helping us think about wage differences between workers with different levels of education. Part two, airing next week, covers his contribution to our understanding of the benefits of living in a better neighborhood, along with some meta-commentary about the importance of a principled, scientific approach to tackling difficult questions.

The Race between Education and Technology

Why does education increase earnings? And why does the return to education vary so much across places and over different periods in history? The college wage premium ranges from 15 percent in Denmark and Sweden to 63 percent in the U.S. and 179 percent in Chile.

(Note – “college wage premium” is shorthand for the average earnings of college graduates divided by the average earnings of workers with no college education. Cross-country comparisons are difficult because systems differ, but most use upper tertiary education rather than vocational degrees to measure the value of college.)

When Harvard economist Richard Freeman wrote The Overeducated American in 1976, the college wage premium had fallen from 55 percent to 45 percent over previous decade. His timing was impeccable. Right after the book was published, the college wage premium began to grow rapidly, quickly outpacing its decline. By the late 1980s, the college premium was above 65 percent, and it continued to grow steadily all the way through the late 2010s.2 Why?

Larry’s key insight was that the college wage premium is the equilibrium “price” of skills in an economy. His 1992 paper with Kevin Murphy, “Changes in relative wages, 1963-1987: supply and demand factors” is one of the most influential economics papers of the last several decades. It has been cited nearly 7,000 times, and the conceptual framework they developed to understand the evolution of wage inequality in an economy was so influential that it is still commonly used today.

Here I will only describe the high-level findings and how they obtained them. If you want to understand the guts of the paper, you can either read the paper itself or read a summary I wrote for a recent chapter of the Handbook of Economics of Education.

If the college wage premium is the equilibrium price paid by employers for a more skilled worker, then we can use Economics 101 principles to predict the impact of changes in supply or demand. All else equal, shifting the skill supply curve outward lowers the equilibrium price. In other words, the college wage premium is lower in Denmark and Sweden because skills are plentiful in those countries. The college wage premium rose rapidly in the U.S. during the late 1980s because the postwar baby boom had fizzled, causing a slowdown in the growth of the college-educated workforce. A college degree is more valuable when it is scarce.

The supply of skills isn’t strictly knowable. But the supply of education can be measured fairly well by tracking the average educational attainment of the population.3 The demand for skills is much harder to observe. Still, even if you can’t observe demand directly, you can predict what might happen if the demand for skills increases, perhaps due to technological change.

Consider the impact of the computer/digital age and the ensuing revolution in information technology. Tools like Microsoft Excel allow you to digitally store information and perform basic computations and other manipulations. If you’re a business owner, keeping track of revenues and costs in a spreadsheet is much more efficient than using a handwritten ledger, and you can more easily calculate the impact on revenue of changing prices or picking a different supplier. That’s the sort of technology that plausibly benefits highly educated workers more than less educated workers. This logic is the origin of the phrase skill-biased technological change (SBTC). You may have heard this term bandied about as an explanation for growing inequality during the 1980s and 1990s.

It is mostly accepted wisdom among economists that the computer and information technology revolution increased inequality.4 To understand why, we must go back to the Katz-Murphy framework. Even though the supply of skills grew more slowly in the late 1980s than in the previous decades, it still grew. The Katz-Murphy framework tells us that – all else equal - growth in the supply of skills would cause the college wage premium to decline. We’ve seen that happen in countries like South Korea, where huge investments in education have led to compression in educational wage differentials.

So why did the college wage premium grow rapidly in the U.S. in the late 1980s even though supply was growing too? Skill demand must have grown faster than skill supply. The only way to reconcile the pattern of growing educational attainment (supply) and a rising college wage premium (the equilibrium price) is that the demand curve must have shifted out more than the supply curve.

Katz and Murphy developed these insights into a formal economic model and fit it to data over the 1963-1987 period. They were able to explain both the decline in the college wage premium in the 1970s and the sharp increase in the 1980s, just using a simple supply and demand model. Goldin and Katz (2007) extend the basic model back 100 years in their magisterial book The Race between Education and Technology, and Autor, Goldin, and Katz (2020) extend it forward to nearly the present day. It doesn’t fit the data perfectly, but it does a darn good job. It’s remarkable that such a simple conceptual framework explains so much about inequality and the wage structure of an economy.

That is the first major contribution that Larry Katz has made to economics. Next week, I’ll talk about Larry’s work on the importance of neighborhoods.

The other top five journals are the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, Econometrica, and the Review of Economic Studies.

The college wage premium has fallen since the pandemic, mostly because of relative wage gains for low-wage workers – see here.

The correspondence between skills and completed education is surely imperfect, but it’s still useful directionally. Countries with higher average levels of education probably have more skilled labor forces. Increases in the college-going rate in the U.S. over the last few decades have surely increased the average skill level of the population. Typically, people compute a measure of “relative supply”, which is the share of the workforce with a college degree divided by the share of the workforce without a college degree.

I say mostly accepted because there is quite a bit of debate about how much of the rise in inequality can be explained by skill-biased technological change as well as debate about the timing of the shift. For a more critical alternative perspective, see Card and Dinardo (2002). They rightly point out some holes in the simple story. My own view is that there are many concurrent explanations for why economic inequality rose beginning in the 1980s, and all of them probably contributed. Advocates and critics of SBTC are mostly arguing about magnitudes.

Colleges continuously tout the "college wage premium" as justifying the high costs of a college degree. But it seems to me that comparing the average earnings of college grads with those of non-college grads is a flawed model in the sense that those who complete college degrees may have other qualities outside of the degree itself that enable them to become higher earners. Your post on the economic value of an Ivy-Plus degree prompted me to think of what the outcome might be if we were able to compare the earnings of people who were admitted to college after high school, but chose not to go on to higher education with those who earned a degree?

Also, not all colleges are created equal--does it matter where/what degrees were earned? Many people are taking on enormous amounts of debt for themselves or for their kids based on their confidence in the college wage premium, but it seems they may be looking only at top-level results that colleges want them to focus on, and not on the probable outcome for their particular situation. Am I missing something?

Very interesting stuff! Perhaps I'm being dense, but it seems to me that the college wage premium is not just the equilibrium price derived from the interaction of supply / demand for "skills". Doesn't it also reflect the magnitude of the skill gap between college and high school students in a given society? Assuming that there are a basket of key skills that a students needs in order to be employable at a given salary (reading, math, teamwork, etc.), in an economy in which the average high school graduate performs at the ~same~ level as the average college graduate on those key skills, presumably the college wage premium goes to zero. Maybe Sweden just has awesome high schools, US has relatively poor ones, and Chile's are, on average, dire?