Welcome to Forked Lightning

A newsletter about education, skills, and the future of work.

Hi everyone! Welcome to my Substack newsletter. I am a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School. I am also a labor economist, and in my academic work I study education, skills, technology, jobs, the future of work, and related topics.

Some of you have been auto-subscribed. If you are not interested in reading this newsletter, no hard feelings! Just click the unsubscribe button at the bottom of this email. Otherwise, keep reading and stay tuned for tomorrow’s post about the benefits of attending an Ivy-Plus college that we found in our study.

I used to write for the New York Times Economic View, a feature in the Sunday business section that brought an economist’s perspective to certain issues (other columnists included Sue Dynarski, Austan Goolsbee, Richard Thaler, Justin Wolfers, Seema Jayachandran, and others – you should check them out, they were really good!)

Then the NYT canceled the Economic View column because it blurred the line between news and opinion (a story for another day).

Since then, I’ve been searching for another way to communicate important ideas from my academic work to a broader audience. This newsletter is my best attempt. I will give you my honest read of the evidence on certain topics. But I’ll also offer my perspective. News and opinion – two great tastes that taste great together (it’s a very bad sign when a commercial you remember fondly from your childhood is described as “vintage”).

College Admissions Paper - Part 1

This morning, Raj Chetty, John Friedman and I released a paper about elite college admissions. Here is the NYT feature story. Here is the main paper page. Here is a direct link to the full paper, and here is a short non-technical summary.

We received internal admissions and attendance records from hundreds of U.S. colleges, including several of the 12 Ivy-Plus colleges (the Ivy league, plus MIT, Stanford, Duke, and University of Chicago), and data on all SAT and ACT test takers between 2010 and 2015. We linked all of it to U.S. tax records, which allowed us to measure family income at the time of application (because parents claim their kids as dependents) and then – eventually – the adult incomes of the students who were admitted to and attended each college.

We first show you a simple fact – applicants from families in the top 1% of the income distribution are more than twice as likely to attend Ivy-Plus colleges, even among applicants with the same SAT or ACT scores. Figure 2A shows this in a simple way (looking at those with an SAT score of 1510, or ACT of 34), and Figure 2B shows it in a fancy way (reweighting the distribution of scores at each family income level to match the distribution of scores for students attending each school).

The question is, why? Do rich kids apply to Ivy-Plus colleges at higher rates? Are they admitted at higher rates? Or once admitted, are they more likely to accept the offer, perhaps because they don’t need financial aid?

The answer is yes to all three, but it’s mostly admissions. We estimate that about 2/3 of the “extra” rich kids at Ivy-Plus colleges are there because of preferential admissions practices. This is an important finding because deciding who gets in is the one thing that colleges can most directly control. If poor and middle-income kids just aren’t applying, you can convince yourself that you’re trying your best but hey, it’s just a very hard problem.[1] The admissions solution is straightforward – just say yes!

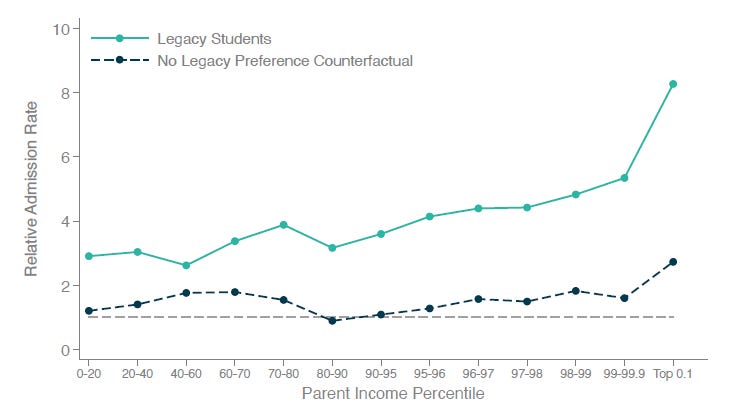

Three factors explain almost all of it. The biggest chunk – about half – is preferential admission for legacies. Legacies are richer than the average applicant. Also, the legacy admissions boost is greater for high-income legacy applicants (see Figure 7b). The second factor is recruited athletes. Again, athletes are richer than average Ivy-Plus student, and they comprise 10% of the total class at such colleges, compared to 5% or less at large public universities.

The third factor is that rich kids receive systematically higher “non-academic” ratings. Selective colleges typically create ratings that group applicants into buckets based on readers’ sense of their summary qualifications. For example, the academic rating includes test scores and GPA, but also AP classes, course difficulty and rigor, and other factors. The “non-academic” ratings vary by school, but typically include things like extracurricular activities, leadership, and community service.

Among applicants with the same SAT/ACT scores, rich kids get systematically higher non-academic ratings (see Fig 8b). Notably this is not true for the academic rating (Fig 8a). This is mostly happening in exclusive private (non-religious) schools.

College Admissions Paper - Part 2

That’s only the first part of the paper! The second part shows the impact of attending an Ivy-Plus college. Do these colleges actually improve student outcomes, or are they merely cream-skimming by admitting applicants who would succeed no matter where they went to college?[2]

We focus on students who are placed on the waitlist. These students are less qualified than regular admits but more qualified than regular rejects. Crucially, the waitlist admits don’t look any different in terms of admissibility than the waitlist rejects. We verify this by showing that being admitted off the waitlist at one college doesn’t predict admission at other colleges. Intuitively, getting in off the waitlist is about class-balancing and yield management, not overall merit. The college needs an oboe player, or more students from the Mountain West, or whatever. It’s not strictly random, but it’s unrelated to future outcomes (there are a lot of technical details here that I’m skipping over, including more tests of balance in the waitlist sample – see the paper for details). We also show that we get similar results with a totally different research design that others have used in past work (see footnote 2).

Almost everyone who gets admitted off an Ivy-Plus college waitlist accepts the offer. Those who are eventually rejected go to a variety of other colleges, including other Ivy-Plus institutions. We scale our estimates to the plausible alternative of attending a state flagship public institution. In other words, we want to know how an applicant’s life outcomes would differ if they attended a place like Harvard (where I work) versus Ohio State (the college I attended - I did not apply to Harvard, but if I did I surely would have been *regular* rejected!)

We find that students admitted off the waitlist are about 60 percent more likely to have earnings in the top 1 percent of their age by age 33. They are nearly twice as likely to attend a top 10 graduate school, and they are about 3 times as likely to work in a prestigious firm such as a top research hospital, a world class university, or a highly ranked finance, law or consulting firm. Interestingly, we find only small impacts on mean earnings. This is because students attending good public universities typically do very well. They earn 80th-90th percentile incomes and attend very good but not top graduate schools.

The bottom line is that going to an Ivy-Plus college really matters, especially for high-status positions in society.

Behind the Curtain

It took us more than 5 years to write this paper. Working closely with our institutional partners at the CLIMB initiative, we linked attendance and admissions records to U.S. tax data. Collectively the CLIMB initiative schools enroll more than one million four-year college students and 2.4 million community college students, representing more than 15% of all undergraduate enrollment in the U.S.

This paper was a monumental effort in terms of partner coordination, data linking, and analysis. We lost years of progress to the pandemic, and at some points I wasn’t sure if it would ever see the light of day. But here we are. I’m excited, and deeply grateful to the many, many people who helped make the work possible.

The paper is 125 pages long. It has 25 main exhibits (6 tables and 19 figures), and another 36 appendix exhibits. As academic researchers, we have a duty (as I see it) to uncover the truth about elite college admissions in America. Fulfilling that duty requires us to produce a paper that is scientific, precise, and faithful to the data. I can’t claim to be unbiased, but I can claim that we tried.

All this means that the paper is very dense. I stand by our choice to prioritize accuracy over approachability, because our primary obligation is to let the data speak.

Consider this newsletter a complementary product. Having told the most accurate story in our paper, I now want to offer my own perspective on our findings. I don’t speak for John, Raj or anyone else on the fabulous Opportunity Insights Team, nor does my writing reflect the views of the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Treasury Department, the College Board, the ACT, my employer (Harvard), the NBER, any of our CLIMB partners, my wife who thinks I am crazy for kicking this particular hornet’s nest, my kids who couldn’t care less about any of this, my research assistant extraordinaire Ivor Zimmerman, or anyone else I haven’t mentioned.

Each day I’ll dig into a different aspect of the paper. Tomorrow I will explain how we estimated the benefits of attending an Ivy-Plus college, and why our findings differ from prior work. On Wednesday I’ll offer my own interpretation of those findings, in particular the role of on-campus recruiting in explaining why Ivy-Plus colleges make such a difference for top-end outcomes. On Thursday, I’ll talk about the practical problem with holistic admissions, which turns a microscope to every detail of an applicant’s life in a futile effort to discern who is most deserving. On Friday, I’ll tell you what I would do if you made me the U.S. higher education czar. So stay tuned.

One final note: this newsletter is named after my favorite poem. It is a reminder to keep pushing, to try to do something useful with myself and the good fortune I’ve been granted. I should probably just relax and enjoy the sinecure of tenure, but I’d rather burn and rave at close of day. Let’s fork some lightning together.

[1] My economist colleagues Chris Avery and Caroline Hoxby and Sue Dynarski and her colleagues have done some important work on encouraging applications to selective colleges. Our sense is that application mattered even more a decade ago, before colleges increased their recruiting efforts and before the Common App became so popular. These days, schools like Harvard are mostly able to find the highly qualified low-income students, but it wasn’t always so.

[2] It might seem totally obvious that Ivy-Plus colleges matter given the tremendous effort families undertake to ensure that their kids get admitted. Yet past work by Dale and Krueger (2002) calls this into question. They look at applicants who are admitted to the same schools, but make different enrollment choices. The idea is that colleges know who the best applicants are, and so their admissions decisions reveal the applicant’s true quality. Using this approach, Dale and Krueger found no impact on earnings of attending a more selective college. In our paper we replicate their approach and similarly find little or no impact on average earnings, but a very big effect on whether you are a very high earner. Dale and Krueger could not have found that in their data because they had a smaller sample and income was top-coded in their survey.

Thanks for doing this. I follow and admire your work. Have cited the "soft skills/ hard skills" paper a lot and use it in research and consulting.

Thanks.

I realize you want to avoid the affirmative action brouhaha, but could you release your graphs showing just the results for whites or whites & Asians combined? It's too hard to look at your graphs and try to guesstimate what percentage of the effect is due to the nominal subject and what due to racial preferences.