Why did rising agricultural productivity destroy farm jobs?

Engel’s law and the future of work

Last week we talked about how the automation of farm work required a lot complementary innovation after the initial breakthrough of steam power, and how that may also end up being true for generative AI.

But why did productivity growth in farming end up destroying jobs? Is job loss an inevitable consequence of technological disruption? The answer depends on whether you think there is something special about food.

Ernst Engel was an unlikely foil for Thomas Malthus, the patron saint of doomers. Malthus famously argued that rising living standards cause population growth, which inevitably leads to immiseration and death as the same pool of resources gets spread across more and more people. This “Malthusian trap” prevented real progress, in his view. Now we know that Malthus was wrong, but it didn’t seem so obvious in 1798 when he wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population.

Engel was a German bureaucrat who studied at the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology in Saxony. He was appointed director of the new Statistical Bureau of Saxony in 1850 amid a time of social unrest. Working class Germans were rebelling against political censorship and the poor economic conditions in newly industrialized urban areas, so Malthus was on the mind.

Engel sought to prove Malthus wrong. In 1857 hew wrote The Consumption-Production Relations in the Kingdom of Saxony, which became the foundations of what is now known as Engel’s Law. He was interested in Malthus’ conjecture that rising living standards would inevitably lead to constraints on the economy’s productive capacity. To put it bluntly, Malthus thought there wouldn’t be enough food to go around.

Engel asked a simple question – how does food consumption change as we get richer? Using data collected on the family budgets of 199 Belgian families, he calculated the share of total income that different types of families spent on food. “Comfortable” families spent 62 percent of their household budget, compared to 71 percent of budget for families who were on social assistance (or “relief”, as he called it). Average income in the first group was twice as high, so they did spend more on food in absolute terms. But they also spent more on everything else, and food declined in relative budgetary importance. His statistical tools were primitive compared to today’s standards, but the results basically hold up with fancier modern methods.

These days, we think about “Engel curves” as expressing the relationship between food expenditure and total expenditure. The figure below from Our World in Data plots the cross-country relationship, with food expenditure is expressed as a share:

Citizens of the poorest countries in the world are spending more than half of their total budget on food, compared to a food expenditure share under 15 percent in rich countries and only 6.7 percent in the U.S.

Engel’s law tells us that a “Malthusian trap” is not inevitable. The total demand for food does not grow in proportion with the population. As societies become wealthier, they devote a smaller share of their total resources to food production, and a larger share to other things, including education, health care, and leisure.

Engel’s law for farmers

Rising living standards are great for civilization, but bad for farm employment. As we got richer and spent a higher share of our budgets on other things, agriculture became a smaller share of economic activity. Pair this with the rapid productivity growth we discussed last week, and the end result was a large-scale destruction of farm jobs.

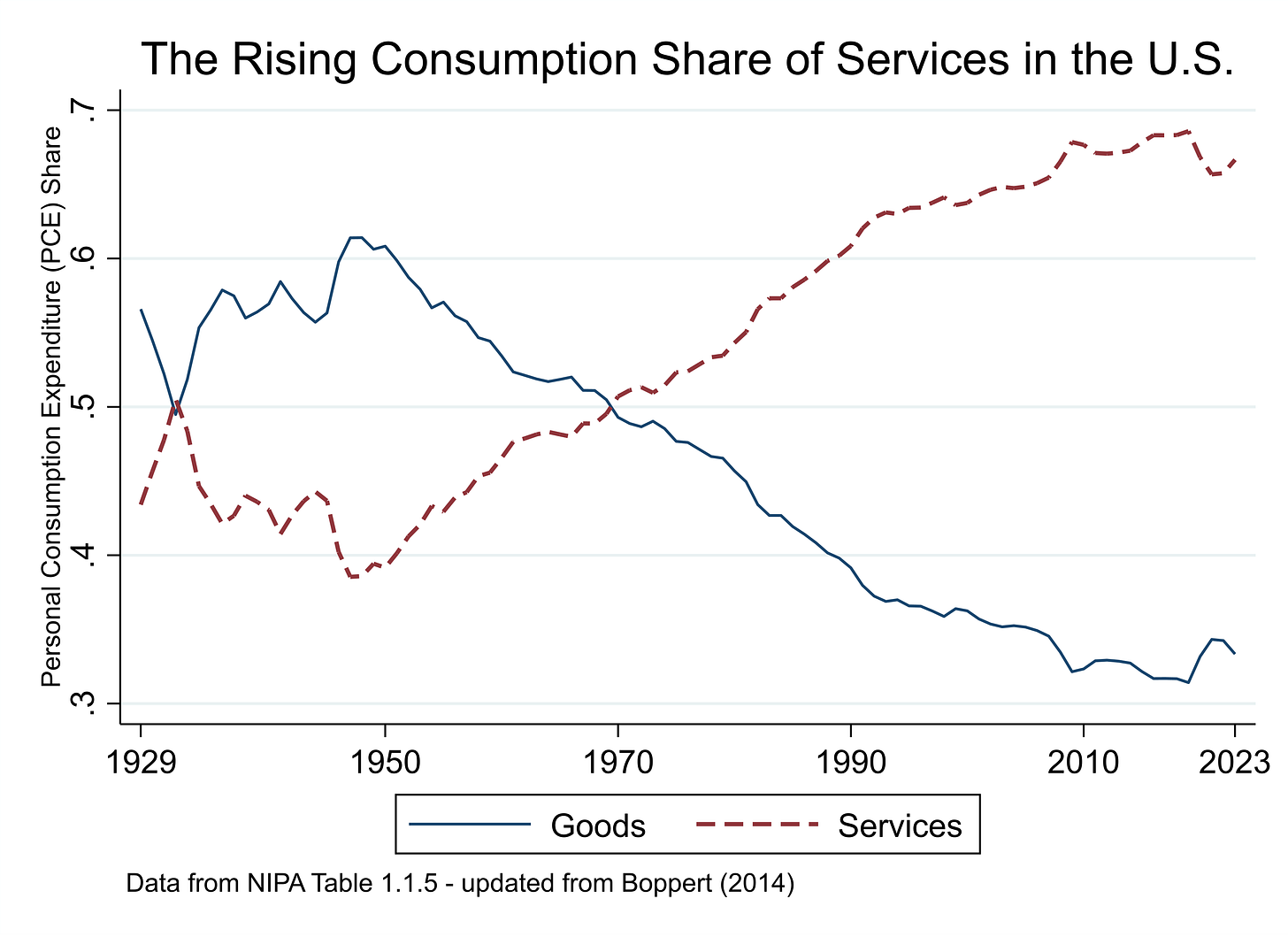

Does Engel’s law generalize to other goods and services? In a 2014 Econometrica paper titled “Structural Change and the Kaldor Facts in a Growth Model with Relative Price Effects and Non-Gorman Preferences” (I do the reading so you don’t have to!), Timo Boppart shows that the U.S. share of consumption expenditure in goods has fallen steadily over time. Using National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) data, I reproduced this key result from Boppert’s paper up through 2023 – see below:

The share of all household spending on goods, which the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) defines as “things you can make, grow, or extract from the land”, fell from a high of more than 60 percent in 1950 to about 31 percent in 2019. It then ticked upward a couple of points because everyone was buying things online during the pandemic. Mechanically this means that U.S. households are spending a higher share of their income on services, which the BEA defines as “actions that people do for someone else.”

Boppart also shows that Engel’s law seems to apply to goods more broadly. The prices of goods are declining relative to services, and poor households spend a larger fraction of their household budget on goods than do rich households.

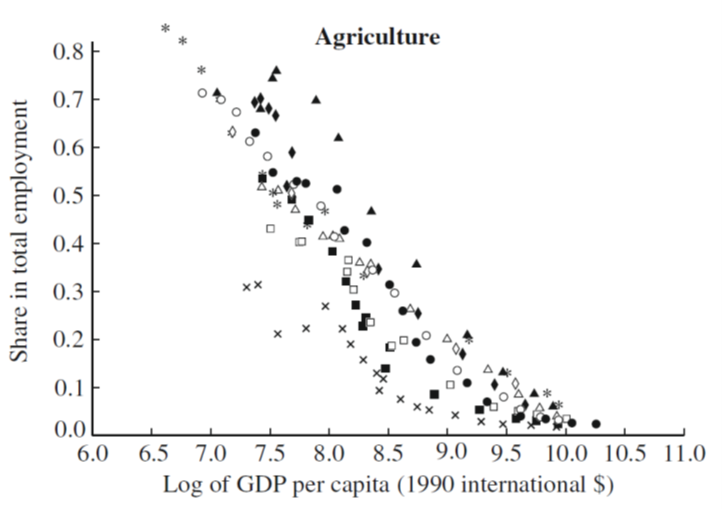

The US, like many other countries, transitioned out of agriculture and into manufacturing, then out of manufacturing and into services. Herrendorf, Rogerson, and Valentinyi study income growth and employment of 10 different currently rich countries over the last 200 years and find a striking similar pattern across all of them. Poor countries start off in subsistence agriculture, then move to manufacturing, then transition to services. See the figures below, which plot employment shares against log GDP per capita:

(Log values of 7, 9, and 11 are about $1k, $8k, and $60k in 1990 dollars, so ranging from very poor to rich).

These figures include the U.S., where manufacturing employment has declined from about 35 percent of all jobs in the U.S. economy in the mid-1940s to less than 10 percent today.

What is the future of manufacturing jobs? Automation fueled productivity growth in manufacturing for most of the mid to late-20th century, in a parallel story to farming (although interestingly, it has slowed down recently). Work by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo shows that each additional industrial robot “hired” in manufacturing costs more than 3 human jobs.

Despite what both Presidential candidates would like you to believe, manufacturing jobs are probably not returning back to their prior levels. There will still be jobs in the manufacturing sector, but they will bifurcate into highly-skilled knowledge work and “last mile” jobs, as they have done in agriculture.

And yet, we aren’t running out of jobs! While manufacturing employment has steadily declined, every category of service sector employment – education, health care, professional services like legal and consulting, and hospitality and eating and drinking establishments – has grown steadily to make up the difference. We don’t have fewer jobs than we used to have, we’ve just had a massive shift away from “making things” to “performing actions for other people.”

Will AI eat the service sector?

Maybe. But it won’t be easy. In both agriculture and manufacturing, we’ve invented technologies that “make things” better or cheaper than people. But for AI to dominate in services, it will have to outcompete human labor in “performing actions for other people”. This is a much harder hill to climb, because in many cases people have strong preferences for customization and variety.

Let’s think about food production again. In subsistence agriculture, the goal is to convert the natural resources of the earth into something edible. The consumer is the producer, and they prefer to consume enough calories so they can live another day. Pretty simple.

Now let’s say you want to make a living off your ability to produce food. You need to sell it to other people. That requires packaging, processing and distribution. In some cases, you might want to combine ingredients to create new foods that can be sold in grocery stores. Food manufacturing is the process of converting raw ingredients that from the farm into products that can be sold in grocery stores and markets. Increasing productivity in food manufacturing means getting the food that people want into their hands at a lower cost.

Most foods are commodities. Do you know what brand of salt you bought at the store? Do you know the name of the orchard that supplied the apples in your fridge, or the farmer who raised the chickens whose eggs you ate for breakfast this morning? For the most part, no. You are interested in a reliable, decent quality product, and you don’t care who makes it. The same logic applies to many generic household items. These are the conditions that lead to economies of scale, capital-intensive food manufacturing, and automation.1

The goal of the food services industry is to move food off the store shelves and into your belly. There are many ways to do that. If you want a pizza, you can buy flour and cans of sauce and cheese at the grocery store, or you can buy a frozen pizza, order one for takeout, or have it made for you in a wood-fired oven at a fancy Italian restaurant. According to USDA food expenditure data, Americans are spending an ever-larger share of their food budgets on eating out. In 2022, about one-third of every dollar spent on food was in food services.

Variety is the spice of life

Lower-income households tend to eat out less, and they are much more price-sensitive at the grocery store, for example by buying generic products over name brands. Even when eating out, they prefer chain restaurants because of cost and reliability. At the high end of the market, food services is all about satisfying preferences for variety. High-income diners don’t want to eat at the same restaurant every night. They want to try that hot new restaurant or buy a fancy new oven and make pizza at home with the family.

As we get richer, we have greater preferences for variety - not just for food, but for a wide range of things. We want customized health care, private tutors, and personal trainers. The distinctive feature of all these jobs is that they cannot be easily commoditized. The appeal comes from personalization, and cookie-cutter service sector products always end up seeming down-market.

When we are buying electricity, flour, or toilet paper, it’s all the same and we mostly don’t care if it’s made by a faceless corporate conglomerate. But there will never be only one author who sells ALL the books – in fact, authors, musicians, and other artists who achieve mass market appeal inevitably get called “sellouts.” We also wouldn’t want one medical practice to employ all the doctors, or one university that everyone attends.

Will AI make the service sector more concentrated? My instinct is that technology will commoditize some services that we now take for granted. For example, having a personal assistant who schedules your meetings and books your travel still feels like a luxury, but in the future AI may be able to do it for everyone.

Still, there will always be a higher end of the service sector, because people don’t like to feel commoditized. This explains the explosion of an increasingly baroque set of new service sector jobs, as Tyler Cowen has documented. The jobs of the future will be increasingly people-facing, not because AI is incapable of impersonating a human, but because the AI’s effort isn’t scarce. Buying the time of a real person makes us feel important.

A hot topic in economics is the global decline of the “labor share”, meaning the share of all national income that is produced by labor rather than capital. A falling labor share is associated with greater automation and more economic power for corporations relative to wage workers. Recent work shows that the decline of the labor share is driven by the rise of large, highly productive “superstar” firms that make intensive use of technology. Market concentration and automation go hand-in-hand.

It is pretty much a tautology that over time employment moves out of sectors where productivity outpaces demand (agriculture) and into sectors where demand outpaces productivity (health care)

>The jobs of the future will be increasingly people-facing, not because AI is incapable of impersonating a human, but because the AI’s effort isn’t scarce. Buying the time of a real person makes us feel important.

This has been already happening, due to outsourcing. I work in IT and I find out 90% is people stuff, like figuring out what customers actually want. The coding we can outsource to a country with low prices.