A data-driven case that AI has already changed the U.S. labor market

A painfully cautious economist tries – and fails - to avoid the AI hype

Welcome back! Last week we talked about the history of machinists and how computers shifted the demands of the job from technical precision to problem-solving and teamwork.

This morning, the Aspen Economic Strategy Group released a paper I wrote with Chris Ong and Larry Summers called “Technological Disruption in the Labor Market.” You can find the paper here. Also, Larry and I will be talking about the paper and about my new survey of generative AI usage in the U.S. at an event at HKS this evening (Monday 10/7). Please come by if you are local – if not, check out the livestream!

This paper originated as a response to the incessant drumbeat that we are in an era of massive technological upheaval. Breathless declarations like these populate the opening paragraphs of many consulting white papers and think pieces, yet they are rarely grounded in hard evidence. Perhaps like other fellow economists, our instinct is that “things are changing faster than ever” is a lazy crutch argument made by people who either don’t know much history or want to sell you something.

We were interested in whether there was any empirical truth to “things are changing faster than ever”. So wwe developed this concept we call occupational “churn” way back in 2017. The idea was to measure the total magnitude of changes in the frequency of different types of jobs over time.

We calculate “churn” in three steps:

1. Compute employment shares for each occupation in each year.

2. Calculate the absolute value of the difference in employment shares for each occupation over a given period.

3. Sum up all the absolute values to get a comprehensive measure of labor market “churn”.

For example:

Protective service occupations like police and firefighters were about 2.1% of all jobs in the U.S. in 2010 and about 1.9% of all jobs in 2024.

The absolute value of the difference between 2010 and 2024 is 0.02 (because |0.019-0.021| = 0.02).

We add those numbers up for all occupation groups to get our measure of churn. An economy where the distribution of jobs was completely stable would have churn equal to zero.1 Higher churn means a greater shift in the job distribution.

When we measured occupational churn in the 2010s, we discovered that things were not “changing faster than ever”; in fact, churn had slowed down in the 2010s relative to the 1990s and 2000s. This was novel, at least to us, because it contradicted popular narratives like the idea that nearly half of all U.S. jobs were at high risk of automation. We planned to write something about it, but never followed through.

When we were offered the chance to write this AESG paper, we thought it was a good time to exhume our “cranky economists tell everyone to calm down” routine.

For the paper we took a very long view, measuring occupation change all the way back to 1880, as early as we have reliable data.2 The figure below shows our measure of churn over the ten-year periods between the fielding of the U.S. Census (and more recently, the American Community Survey):

The three-decade period from 1940 to 1970 was the most volatile period in the history of the US labor market.3 The transition out of agriculture was accelerating, with the employment share in farming declining by more than 13 percentage points between 1940 and 1970. There was also a significant compositional shift in blue-collar jobs, with rapid growth in construction and repair work but a big decline in transportation jobs, which was driven by the shift toward personal automobiles and away from railroads. Professional and administrative-support occupations also grew rapidly in the middle of the 20th century.

After 1970, the US labor market entered a forty-year period of relative quietude. The 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s (2010-2019, so pre-pandemic) were among the least volatile periods in history.

We thought this is where the story would end, with us telling everyone to calm down.

But then we started looking at data from the post-pandemic labor market, and we were forced to revisit our prior beliefs. We found four reasons to think that things might be different this time.

The labor market is no longer polarizing

One of the most important labor market trends in the 1980-2010 period has been “polarization”, meaning employment growth in both low- and high-paid jobs and declining employment in the middle. A 2006 paper by Autor, Katz, and Kearney was (I believe) the first to document this phenomenon, which has since been found in many other countries. The idea was that computers automate routine physical and information processing work (think machinists and bank tellers), which caused employment in these and other middle wage jobs to decline. At the same time, we saw growth in basic manual labor and personal services occupations, which don’t pay very well but are difficult for machines to automate.

The thirty-year polarization trend stopped in the middle of the 2010s, as the figure below shows. Not because jobs in the middle have come back, but rather because only high-paid jobs are growing anymore (we kept the job categories constant over the decades.) The pattern after 2016 looks more like “upgrading” than polarization.

The decline of personal services occupations

A big driver of labor market polarization was the growth of low-paid service sector jobs like home health aides, food preparation and service, cleaning and janitorial services, hair stylists, fitness instructors, and childcare workers.

Employment in service jobs grew very rapidly from 1990 through the early 2010s, and has either flatlined or fallen since, as the figure below shows. While the pandemic was a big factor – see the drop in food prep and personal services between 2019 and 2020 – the decline started earlier, around 2014.

The boom in STEM employment

We are experiencing incredible growth of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) occupations in the U.S. As the figure below shows, STEM increased from 6.5 percent of all employment in 2010 to 10 percent in 2024, an increase of more than 50 percent. Growth has been especially rapid in the last five years. It’s concentrated mostly in computer and software jobs, but we’ve also seen growth in engineering and science occupations.

The figure also shows rapid employment growth in business and management jobs. The fastest growing occupations in that category are science and engineering managers, management analysts, and other business operations specialists. This is especially striking because STEM employment declined slightly between 2000 and 2012. At the time I argued that this was due to an increased emphasis on social interaction in professional work. I still think that’s true, but STEM has come back with a vengeance.

The growth of STEM and high-tech management jobs coincides with increased capital investment in AI-related technologies. Spending on software and information processing equipment currently sits at about 4 percent of GDP, which is higher than at any point since the dot-com bubble in 2001. Private R&D spending is currently at an all-time high of about 2.7 percent of GDP. Much of this spending is directly related to STEM hiring, as well as investments in computing capacity like data centers.

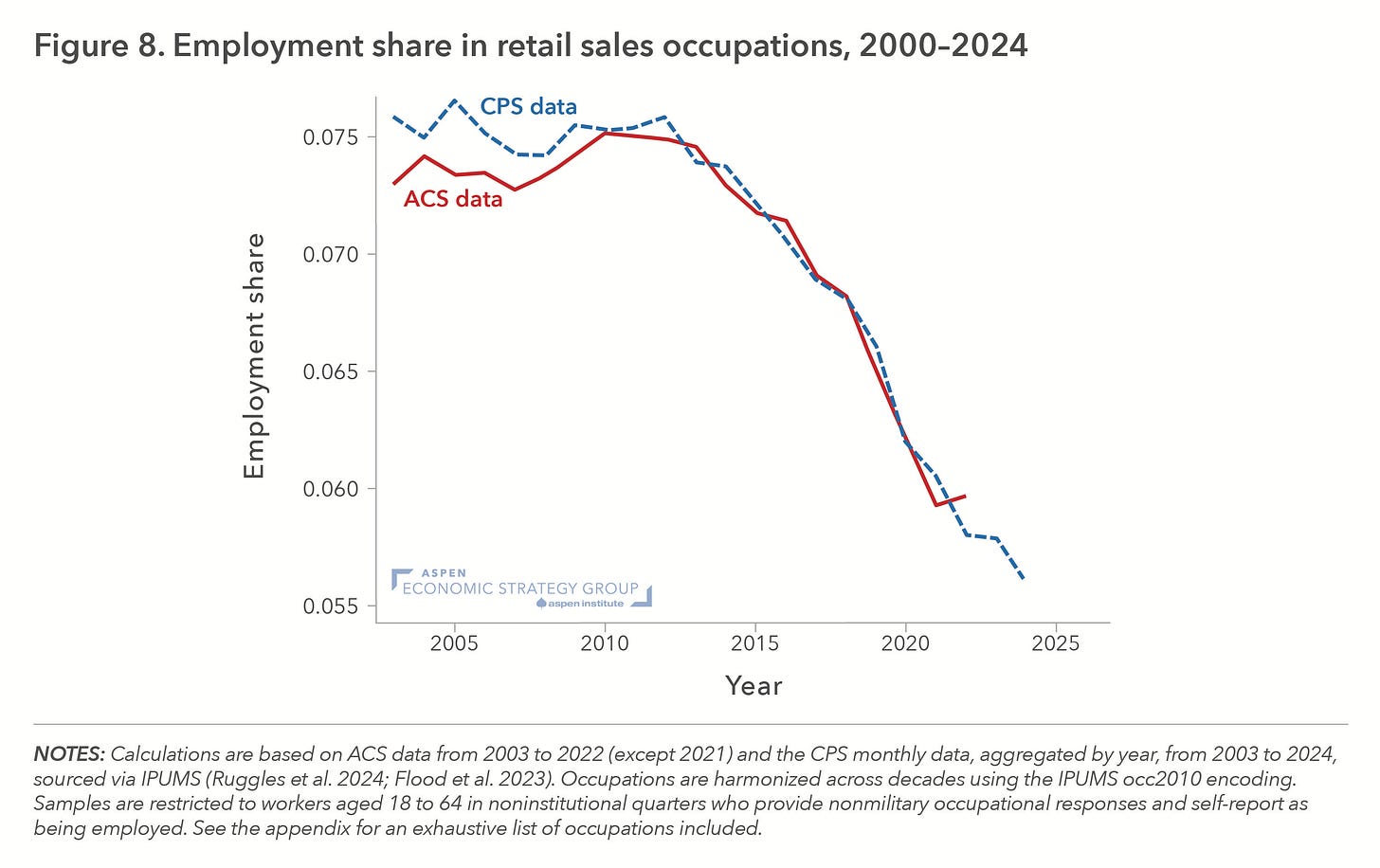

Retail sales jobs are disappearing rapidly

The final labor market trend we uncovered was a very rapid decline in retail sales jobs, show in the figure below. Retail sales hovered at around 7.5 percent of employment from 2003 to 2013 but has since fallen to only 5.7 percent of employment, a decline about 25 percent in just a decade. Put another way – the U.S. economy added 19 million total jobs between 2013 and 2023 but lost 850 thousand retail sales jobs. The decline started well before the pandemic.

How much do these recent changes have to do with AI?

Since ChatGPT has only been around a couple of years, it is probably too early to see any direct impact of generative AI on the labor market. Still, so-called “predictive” AI has been around a lot longer than generative AI. Companies like Amazon have been using predictive AI tools like machine learning since the mid 2010s to produce personalized prices and product recommendations, optimize inventory management, and other innovations (see my NYT column about this back in 2020 if you are interested).

Could predictive AI be responsible for the decline in retail sales jobs? It’s hard to say for sure, but I would note that online retail has been around a long time (remember Pets.com?). Why did retail jobs start to decline in the early 2010s specifically, after holding steady for more than two decades after the dot com boom?

There were many important AI developments in the early 2010s. Big tech companies started investing heavily in AI in response to the rapid performance improvements realized by deep learning models (like AlexNet) that were trained on Nvidia-produced GPU chips. On the commercial side, Amazon bought Kiva Systems in 2012 (now called Amazon Robotics), a company that uses AI-directed mobile robots to stock and manage inventory.

Also, it’s surely true that the increase in STEM employment was at least partially driven by corporate investments in AI. Interestingly, “stockers and order fillers” and “light delivery service truck drivers” have grown by 60 percent and 29 percent respectively since 2023, compared to 14 percent overall job growth. None of this constitutes proof, but it is a decent circumstantial case that AI has already made its presence felt in the US labor market.

The broader context is a decades-long trend of occupational upgrading in white collar work. Administrative and clerical jobs like financial clerks and secretaries have collectively declined from 7.8 percent of all jobs in 1990 to only 3.3 percent today. At the same time, management and business jobs have grown rapidly. Some of this is probably relabeling, but it also reflects a genuine shift away from routine office functions and toward analysis, strategy, and decision-making.

I can see a future where AI commodifies most white-collar office work. Tasks like writing a business plan, organizing the office calendar, and generating and editing software code can be done easily and cheaply by current AI models. I doubt that future is arriving as soon as people think for the reasons I wrote about a few weeks ago – adoption happens slowly, and there are a lot of kinks to be worked out. But it seems likely to happen eventually, even if we have another dot-com style bust in between.

I am not predicting an AI boom. But overall, I think we need to consider the possibility that the ground is moving under our feet.

The virtues of this measure of labor market change are that it is symmetric, it holds overall employment constant, and it covers all occupations and treats them all equally. The major limitation is that it only accounts for occupation change, not other big sources of disruption such as the need to relocate from farms to cities for a job in industry, or more recently the shift toward remote work. Don’t think of it as a comprehensive measure, but rather as a good start.

A serious complication for analyses like these is how you consistently categorize occupations over time. The paper and the technical appendix get into all those details, but the TL;DR is that we had to aggregate occupations broadly enough to give us consistent data. There were no occupational therapists in 1880, but there were health professionals like doctors and nurses.

The 1880-1900 period was extraordinarily disruptive, mostly because of the transition out of farming (no data is available for 1890, and this lack of data may overstate the pace of change).

"Why did retail jobs start to decline in the early 2010s specifically, after holding steady for more than two decades after the dot com boom?"

Two decades? - internet access pre 1995 was primitive and throttled by the attempted AOL/Compuserve hegemony. Sure online sales started to grow with the arrival of Amazon after Win 95 made internet access a doddle, but exponential growth from zero looks linear for quite a while.

Retail only needed to pay attention after 2008 when pocketbook problems concentrated our attention on the benefits of online sales. So the decline in retail jobs started at that point - 5 years rather than 20.

What about the widespread adoption of mobile phones with unlimited data and ubiquitous shopping apps in the 2010's so that people can now shop wherever they are, instead of only In front of their computer?