The unintended consequences of test optional

Like height on a dating app, the question is what SAT score will make colleges swipe right?

Welcome back! In the first installment of this long post on college testing, we dove into the history of the SAT and the social context in which it was implemented nearly a hundred years ago. I also showed you that SAT and ACT predict success in college and later in life, even after accounting for high school GPA and other information on an application.

Last week, Yale followed Dartmouth’s lead and announced that they would once again require applicants to submit standardized test scores for college admissions. Moving in the opposite direction, the University of Michigan declared that their temporary test-optional policy would remain permanent for future classes.

The Yale announcement cited as a rationale something that we found very clearly in our own study of college admissions – SAT/ACT scores, while not perfect, are fairer to low-income applicants than essays, extracurriculars, and other parts of the application. They sum it up nicely: “Our researchers and readers found that when admissions officers reviewed applications with no scores, they placed greater weight on other parts of the application. But this shift frequently worked to the disadvantage of applicants from lower socio-economic backgrounds.”

Yale emphasizes the relative fairness of college test scores. Test optional advocates might respond that they are not against SAT/ACT scores, they just want to empower students to make their own choice. Choice is good, right?

If you asked me to advise a young person applying to Harvard about whether to submit their SAT score, I honestly wouldn’t know what to tell them. And I’m supposed to be an expert!

There are two things that make it hard. First, colleges have different expectations for different types of students. Some of these differences have been adjudicated by the Supreme Court, but others are just garden variety class balancing. Public school students from the Massachusetts suburbs probably have a harder time getting into Harvard than similar students from other parts of the country. Because colleges balance their admitted classes on multiple dimensions, it’s hard to know where you stand unless you know the scores of other comparable applicants.

Second, even if you do know where you stand, you don’t know how your peers will behave. If only the very highest scorers are submitting, you don’t want to look bad compared to them. They are all thinking that way too. The definition of a “good” score is person-specific and is a moving target from year to year. As fewer people disclose their scores, fewer people will want to be compared to who is left. Average scores among those who submit will ratchet upward over time, especially on the low end.

A quick glance at the data suggests this is exactly what is happening. Using data I downloaded from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), I looked at 25th/75th percentile scores and score submission rates at selective colleges for the fall classes of 2018 through 2022 (the latest year for which data is available). At most schools, test scores were required for the classes of 2018 through 2020, but optional for the classes of 2021 and 2022.

At Harvard, about 70 percent of applicants in the classes of 2018-2020 submitted an SAT score, compared to only 55 percent for the classes of 2021 and 2022. We see drops of similar size at schools like Yale, Stanford and Dartmouth, and even bigger changes at highly selective but non-Ivy-Plus schools like Tufts, where score submissions dropped by more than 20 percentage points. Despite this huge drop in submissions, the 75th percentile SAT scores for applicants to Yale, Harvard, and Stanford stayed exactly the same (780 for verbal, 800 for math). But the 25th percentile increased by 20-30 points for all three schools. At Tufts, the 25th percentile SAT scores increased by 30 to 40 points, while the 75th percentile barely budged.

Only the “high” scorers submit their scores, which increases average scores, which then changes the definition of a “high” score the following year.

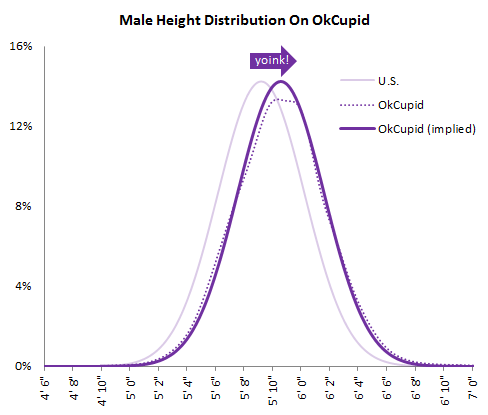

This phenomenon is well-understood in any setting where disclosure is voluntary, ranging from CarFax reports for used cars to restaurants displaying inspection grades in the window, to online dating. A fun graph from OKCupid’s Dating Blog shows you what happens when men can choose whether to disclose their height in their online profile.

The graph is shifted substantially to the right, which tells you what you already know – men lie about their height to get online dates! However, the implied line shows you what you would expect to see if every man exaggerated his height by 2 inches, so that average height increases but is still normally distributed. The missing mass (e.g. the gap between the dotted line and the dark line) is largest at 5’10 and 5’11, which are average heights worldwide but perceived as not quite good enough to get a “swipe right”.

Is no news good news? That depends on who is delivering it

The bottom line is that whether to submit your score is a highly strategic choice that depends a lot on who you are, where you are applying, and what other people like you are doing. Strategic complexity favors well-prepared applicants.

Low-income, first-generation students may have a harder time solving for the equilibrium. In particular, they may not submit scores when they would actually benefit from doing so.

Understandably, they might look at public data on SAT scores by college and only submit if they are above the overall average. But admissions officers understand that a 1400 SAT score means something different coming from a disadvantaged applicant versus an uber-prepared prep school kid. If applicants don’t adjust for the thumb on the scale they are receiving, they will make the wrong decision.

Skeptical? I can show you that this is happening now, using Dartmouth’s own analysis of their admissions data from 2017 to 2022. To its great credit, Dartmouth commissioned four of their own faculty to study the impact of test-optional on admissions.

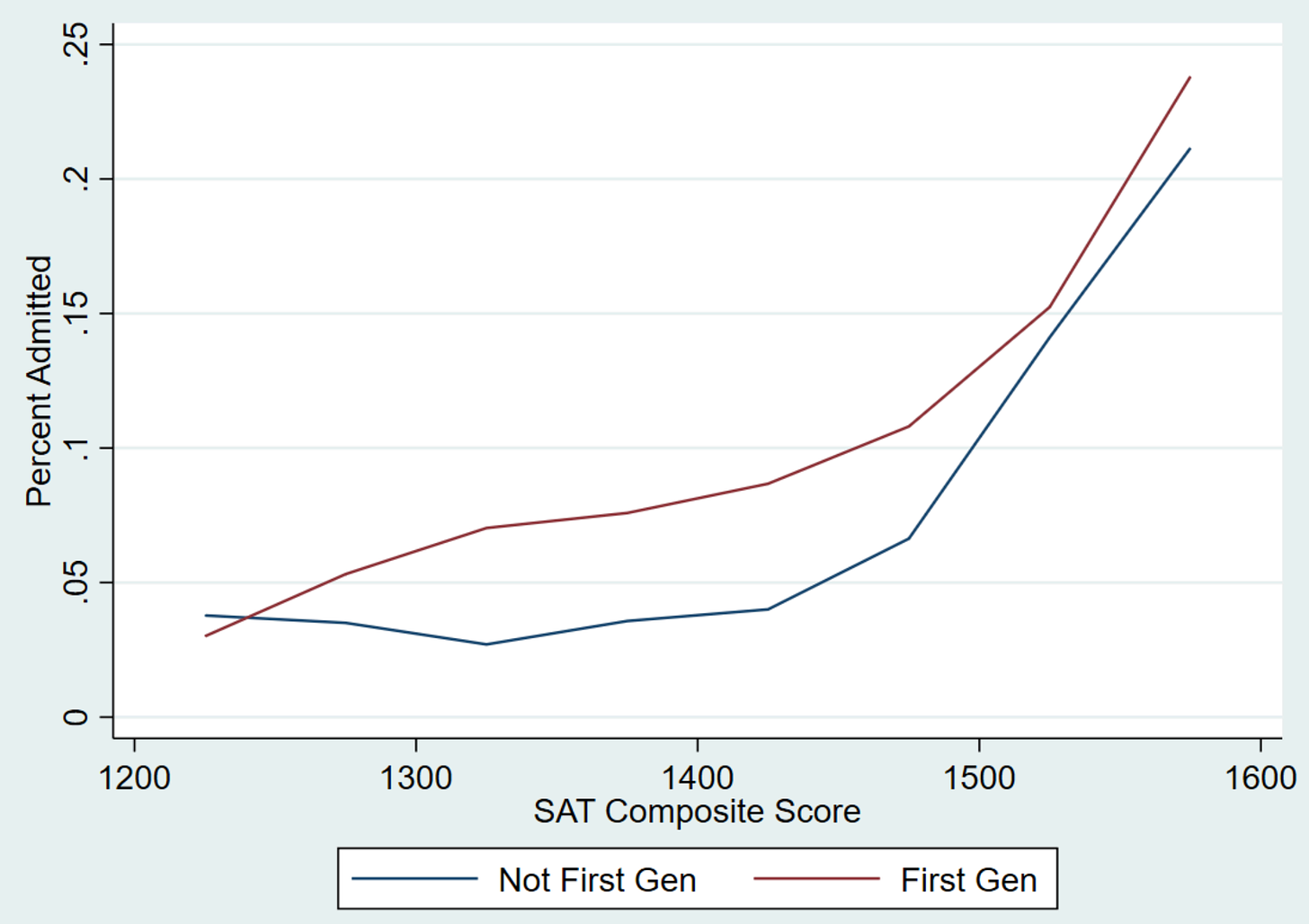

The figure below plots the probability of being admitted by SAT score, separately by first-generation college student status, for applicants in the 2017-2018 “test required” cohorts. You can see that first-generation students are much more likely to be admitted at any given SAT score, with the biggest advantages for students in the 1350-1450 range. According to the IPEDS data I cited earlier, the 25th percentile SAT composite score at Dartmouth in the 2018 and 2019 cohorts was about 1430.

Applicants in the 2021 and 2022 “test optional” cohorts who scored a 1430 have been looking at the data and thinking “I’m at the 25th percentile, I shouldn’t submit my score”.

The Dartmouth data suggests that this is the wrong decision for first-generation college applicants. The figure below (6c in the paper) plots the probability of admission in the test-optional (2021-2022) cohorts for students who submitted a score, compared to a special subsample of applicants who initially submitted scores but then asked admissions not to consider them. The admissions office blinded themselves to the data in their process, but retained it in their records.

At scores of 1430 and above, the first gen applicants who submitted were more likely to be admitted than those who did not submit. The penalty for not submitting SAT scores was especially large for first-gen applicants scoring 1500 and above.

The study also found that first-generation, low-income applicants were more conservative overall about the decision to submit scores. For example, they estimate that only about 70% of first-gen college students who scored a 1500 submitted their score, compared to 90% of all other applicants - Figure 5c in their paper shows the full distribution. Another recent paper finds similar patterns in a broad range of schools.

Putting this all together, the Dartmouth report concludes that “test optional” harms low-income, first-generation applicants and widens inequality in admissions.

This quote from their report sums it up well: “These data imply that there are hundreds of less-advantaged applicants with scores in the 1400 range who should be submitting scores to identify themselves to Admissions, but do not under test-optional policies.”

Reasons this analysis might be wrong

A cynical reason for selective colleges to prefer test-optional is that it boosts application numbers, which lowers their admission rate and increases their perceived selectivity. A more principled reason is that test-optional may encourage more low-income, first-generation college students to apply in the first place. Indeed, a very nice recent paper studied the rollout of test-optional policies at small liberal arts colleges over the last few decades and found that it modestly increased diversity.

If test optional policies increase applications among low-income and first-gen students, an increase in the applicant pool might make up for the harm caused by voluntary disclosure. However, the figure below from the Dartmouth paper shows no change in the distribution of neighborhood income across test-required and test-optional application cohorts.

I think this is probably because schools like Dartmouth have national reputations and are already getting a lot of low-income students to apply. We also found in our college admissions paper that low-income students were not less likely to apply than other students with similar SAT scores (see Figure 3).

A final caveat is that the criticisms above don’t apply when colleges simply refuse to consider SAT/ACT scores, e.g. test-blind rather than test-optional. This is the current policy of the University of California system, although that is currently being contested by different groups within the UC system.

Still, I believe that test-required is a better and fairer policy than either test-optional or test-blind. I don’t mean to say, however, that admissions should only be based on test scores, or that colleges should simply take the highest-scoring applicants in order. Rather, selective colleges should require SAT or ACT while also placing a significant thumb on the scale for low-income, first-generation college applicants.

The virtue of SAT and ACT is their universality. Because the competition for college admissions has such high stakes, wealthy families will exploit any advantage, including buying access to unusual experiences and activities that are unavailable to ordinary families. By making college entrance exams universal and fair, we allow talented poor kids to earn the kind of distinctiveness that money can’t buy.

If you care about merit why not also mentioned how unfair legacy admissions are? Or the huge boost in admission rate given to kids from

extremely rich families even after adjusting for sat scores?

Or the costs to millions of average kids who are now required to take this newly required high stake sat tests?

"By making college entrance exams universal and fair, we allow talented poor kids to earn the kind of distinctiveness that money can’t buy." This is an odd statement. Is a high SAT score a distinction that is earned? When we say that someone has earned something we generally mean they have worked for it, and that it is the product of sustained effort. A high SAT score is not earned in that sense.

I believe that a rational college admissions should be designed to help students find the college that is the optimal fit for them, whether it is Harvard or Washington U. or Reed or Morehouse. Prof. Deming seems to assume that all students should try to attend the most selective and prestigious school they can get in. Why? So that they will have a better chance of getting a job with McKinsey or Goldman Sachs. These are the "high stakes" to which he refers. His vision of academia is zero-sum and hierarchal. Harvard's purpose is to maintain its position at the top of the heap and choose which 18 year olds will be their generation's super-elite. And because Harvard is choosing elites, it follows that admissions should be based not merely on who is likely to do the best at Harvard, but on Harvard's notion of what desirable elites should look like in the U.S. That means "talented poor kids" should be given the nod over talented upper-middle class kids, even when Harvard knows that the talented upper-middle class kids are likely to perform better academically.

I doubt that Ivy League admissions policies really matter that much to life outcomes, notwithstanding Prof. Deming's waitlist study. Higher education in most other countries is much more stratified. Going to Oxbridge or one of the grande ecoles is a bigger advantage than the Ivy League + Stanford because there is a larger gap between them and lower tier schools than in the U.S. Ending up at Swarthmore or Chicago or Rice or UVa instead of Princeton is not much of a disadvantage.