Welcome back! Today is the first of a two-part series on office jobs. Before diving into the details of how new technologies have disrupted white-collar work, it’s worth stepping back and asking – what is the purpose of these jobs anyway? Farmers and machinists make things that other people find useful. Doctors and nurses heal sick people. What do project managers and administrative support specialists do all day, and does it have any social value?

Somebody’s got a case of the Mondays

If you’re feeling skeptical, you can tap into a rich cultural narrative that links the growth of office work to societal decline. David Graeber railed against the tremendous growth in professional, managerial, and clerical jobs over the last century in his famous treatise on “bullshit jobs”. In Office Space, Peter contrasts the soul-deadening monotony of his well-paid 9-to-5 office job at Initech (“I’d say, in a given week, I probably only do about 15 minutes of real, actual work”) with the simpler, happier life of his neighbor Lawrence, who works in construction. Frank Sobotka from The Wire famously said “We used to make shit in this country, build shit…now we just put our hand in the next guy’s pocket.” And both presidential candidates are talking constantly about the need to bring manufacturing jobs back in America, so we can “build shit” again (my words, not theirs).

Still, let me try to convince you that office work is underrated. The output of many white-collar jobs is not a physical product, but rather improved communication with coworkers, clients, and organizational leaders. Better communication ensures that the right people are doing the right tasks, and better transmission of valuable information improves managerial decision-making.

For as long as humanity has existed, we have been communicating with each other. Speech itself originated a bit over a hundred thousand years ago, and we started using symbols like petroglyphs and cave drawings somewhere around 30,000 BCE. Early human drawings may have had symbolic and religious meaning. But humanity’s success as a species has its roots in the economic value of communication.

As cultural anthropologists like Joe Henrich have argued, early humans faced extreme evolutionary pressure to coordinate and work together. Hunter-gatherer societies relied on diverse and unpredictable food sources, and cooperation allowed them to pool resources directly but also to share information such as where certain plants grew or how to hunt certain animals. Henrich argues that culture is our greatest strength because it allows us to transmit knowledge and traits through social learning and group norms rather than through genetic selection, which takes much longer.

The economic value of communication

Communication technologies are economically valuable for two reasons. First, a thicker communication network increases the chances of connecting willing buyers and sellers and of matching workers to the jobs and tasks that suit them best. For example, the telephone made it easier for businesses to find customers (and vice versa) and for job seekers to apply for positions that they may not have otherwise known about. Better matching increases the size of the economic pie, as David Ricardo showed more than 200 years ago with the classical theory of comparative advantage. Second, communication technologies facilitate the flow of information, which improves the quality of decision-making. Printed books, telephones, radio, and other innovations are all ways to store information so that it can be more easily transmitted between people. Knowledge is power, as they say.

Many of the most disruptive inventions in human history were mass communication technologies. Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press enabled the rapid production of books, which democratized access to knowledge but also led to social upheaval (e.g. the Protestant Reformation). The invention of the radio in the late 19th century brought popular culture to the masses, but it was also a great propaganda tool during the wars of the early 20th century.

You might think that new technologies would eliminate the need for jobs that facilitate communication, but instead the opposite has happened. The printing press made highly trained scribes less valuable, but it created new categories of work (writers, printers, book salespeople) that supported mass communication. Improvements in communication technology tend to increase the total demand for communication, because they enable us to converse with more people and spread our ideas more widely.

Fast forwarding to the present, we see that many jobs in the U.S. economy exist almost entirely to facilitate communication and improve the flow of information. Stenographers and typists create written records of speech to memorialize meetings and court proceedings and to deliver messages. Editors, reporters, news broadcasters, and audio and visual technicians communicate information in various forms to an audience. Business analysts and consultants analyze and interpret information in order to improve organizational decision-making.

Because the human need for communication is nearly infinite, new communication technologies tend to create jobs as fast as they destroy them.

The case of telephone operators

One concrete example of this dynamic comes from a recent paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics by James Feigenbaum and Daniel Gross on the rise and fall of telephone operators.

Alexandar Graham Bell famously patented the telephone in 1869, although whether he actually invented it rather than simply being the first to file is a matter of some controversy. The Bell telephone company was created in 1875 as a corporation whose primary purpose was to protect Alexander Graham Bell’s patent rights from commercial competitors. The CEO of the Bell telephone company was not Alexander Graham Bell himself, but rather his future father-in-law Gardiner Greene Hubbard, a prominent lawyer who had tried without success to break Western Union Telegraph Company’s monopoly by nationalizing the telegraph system through the U.S. Postal Service.

Hubbard had also invested in Thomas Edison’s phonograph, which didn’t work very well. But he struck gold with the telephone. At first, the telephone was a mostly local operation. But the Bell telephone company soon merged with New England Telephone and Telegraph Company to form National Bell, and then it became American Bell in 1880 after a substantial infusion of capital.

(Hubbard sold his stake and created a club for wealthy people who wanted to explore and travel the world, which became the National Geographic Society.)

American Bell then created a nationwide long-distance telephone network through a subsidiary company called the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). AT&T became so big that it subsumed American Bell, like a child taking over the family business. Within a decade, AT&T became a near-monopoly provider of telephone service in the United States.1 By 1920, AT&T had become America’s largest employer, and most of its employees were telephone operators. According to Feigenbaum and Gross, the U.S. telephone industry collectively employed more than three hundred thousand people and connected nearly 65 million calls per day.

Why did AT&T need to employ scores of people to operate telephone lines? Because the number of possible connections scales very rapidly in the number of users. If only two people have a telephone, there is only one connection to make. With three people, there are three possible connections (1 and 2, 1 and 3, 2 and 3). With four people, there are six possible connections, and so on (the formula is (N*(N-1))/2, where N is the number of users). That’s almost fifty million telephone lines for a city of ten thousand people!

Rather than building 50 million one-to-one connections, AT&T and its subsidiaries built central exchanges that connected each telephone to a switchboard. Operators would connect the calls manually by plugging a patch cord into the receiver’s socket on the board. When exchanges got bigger, they started assigning telephone numbers rather than just asking for people by name.

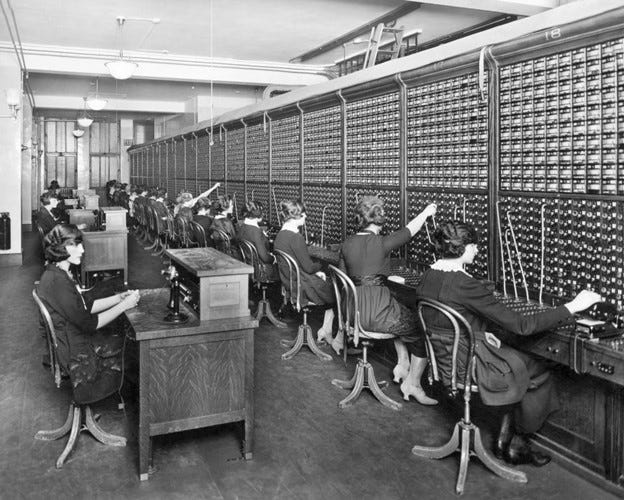

Here is a picture of a telephone switchboard in 1915:

As you can see from the photo, telephone operators were mostly young women. While the job paid relatively well and was seen as superior to factory work, it was brutally fast-paced and demanding. According to internal AT&T memos dug up by Feigenbaum and Gross, the turnover rate of telephone operators exceeded 40% per year. In April 1919, 8,000 operators at the New England Telephone Company went on strike for five days, which shut off nearly all telephone access in New England. The worsening of job conditions was probably a natural consequence of the increasing complexity of the switchboard system. The more phone calls people wanted to make, the more unmanageable the job became, and the greater the incentive to automate call switching.

Rotary phones – so soothing, yet so destructive

If I had to guess at the age of my reader base, I’d say fewer than half of you have ever used a rotary phone. My grandparents had a rotary phone attached to their wall when I was a kid, and I remember being fascinated and oddly soothed by the sound and feeling of making a phone call.

Much later I learned that rotary phones were a not-so-silent killer of jobs. Each turn of the rotary dial sends a series of electrical pulses that correspond to the number being dialed, which then physically moves mechanical switches to complete an electrical circuit based on the combination of numbers that are dialed. The rotary phone directly replaces a telephone operator by sending primitive “code” from your fingers to the switchboard, connecting callers without third-party intervention.

In 1917 AT&T began recommending that its operating companies adopt mechanical switching in large cities. Feigenbaum and Gross study the period between 1910 and 1940 when most major cities switched over to rotary dial service, see their figure below:

Employment of telephone operators peaked in 1920 and declined rapidly thereafter. Using historical data on the timing of “cutovers” from manual to mechanical switching, Feigenbaum and Gross estimate the impact of automation on employment and other outcomes in cities where telephone operator jobs disappeared.

They find that mechanical switching put incumbent telephone operators out of work, with much larger effects for those who were over age 25. Among those who switched to a different job, they moved to slightly lower-paying occupations. Women who were already in the job were harmed.

However, they find no change in employment for young women who graduated from high school right around the time of mechanical switching and would have likely become telephone operators. Even though these jobs nearly disappeared overnight, young women moved on easily to other occupations.

Complexity of communication and the ratchet effect

While the authors can only speculate about the exact reasons, a likely explanation is that many of them moved into other jobs that used their communication skills. Feigenbaum and Gross find that most of the employment shift was accounted for by two occupations – waitresses, and typists and secretaries.

The figure below shows how employment shares changed for telecommunications operators compared to typists and secretaries (NB we cannot easily disaggregate telephone operators from the broader category of telecom, which includes staffing answering services and other similar jobs).

Employment of typists and secretaries grew rapidly between 1910 and 1950, the exact period over which telephone operator jobs were being automated. This is probably not a coincidence. By enabling communication at a distance, the telephone created many new employment possibilities.

For example, the easy availability of co-workers and clients by telephone probably accelerated the pace of office work, leading to an ever-larger volume of communications that needed to be managed. This expanded secretarial work beyond typing. Companies increasingly needed secretaries to screen and route calls, to take transcriptions of calls and meetings, and to coordinate such work more generally. Mechanical switching made communication by telephone cheaper and more reliable, expanding its use in business.

Next week we’ll talk about the second half of the chart above. After growing so rapidly for so long, what happened to secretaries?

AT&T accounted for about half of all telephones in the early 1900s but eventually acquired almost 80% of the market by the early 1930s. The network of companies acquired by AT&T was known as the Bell System, and AT&T itself was not-so-affectionately dubbed “Ma Bell”. AT&T was eventually broken up by regulators, but not until 1984, more than a hundred years after its founding.

When comparing America to its poorer European peers, like Italy and Spain, which occupations are to blame for their poor performances?

Are their mechanics worse at fixing cars? Are there teachers not as good at instructing students? Are there builders not as good at hammering nails?

Or is it that their capital is allocated less efficiently? People like to make fun of email jobs as bullshit, but living in a country where your bullshit jobs are done well seems to matter a lot!

Can you also talk about the inequality effect of the shift?